In one short sentence Our Lord summed up for us the whole scope and meaning of his life on earth: "I am come to do the will of him who sent me."

In these few words He has traced for us the most complete and most accurate portrait of each and all of the saints, whether they be the martyrs of the early Church watering the earth with their blood that the seed of the Word of God might spring up amid the ruins of a decayed civilisation; or the wonder-workers of the Middle Ages, raising their voices above the clash and din of warfare, and startling men by the very force of their miraculous powers; or the gentler race of men, such as St Francis de Sales or St Alphonsus Liguori, combating error by the milder weapons of their pens and persuasive eloquence, none has ever done other than the will of Him who sent them. But times change, and in each varying scene of the world, sanctity, like everything else, has donned a different outward garb.

When the great French Revolution swept away nearly all the old landmarks, the generation of saints who arose, seemingly from the very force of that mighty social earthquake, differed widely from the saints of old, not, indeed, in their essential holiness, but in its outward expression and the setting amidst which their sanctity was worked out.

They were no longer men set apart from their fellows, marked by unmistakable signs and tokens; they lay, as it were, hidden, the leaven leavening the mass. In most cases it was death alone that drew back the curtain that hid their virtues from an indifferent or scoffing world. To few was it given to attain a world-wide reputation like the Curé d Ars; but who shall count the number of hidden lives, already crowned by the Church, or about to be so honoured?

Such was the life of Sister Marie Celeste of the Will of God, whose years on earth were passed in the seclusion of her own home, or the still more restricted solitude of the cloister. But the fact that since her death God seems to be making known His Will, by evident signs, that he wishes her to emerge from her hiddenness, has made it appear desirable that the doors of the cloister that sheltered her should be opened, and that the varying scenes of her life therein should be shown as an encouragement to those, both within and without the walls of the convent, who have to live an ordinary life amidst more than ordinary trials and contradictions.

Most lives of cloistered nuns seem of little if any help to others, for the grille is kept hermetically sealed after as before their death, and a very distorted picture of the soul's pilgrimage is all that is given, from the very fact that it is merely a series of vignettes on a colourless background, with no discernible surroundings. For this reason we have determined to take our readers in spirit behind the grilles, and to show them Sister Marie Celeste as she lived and moved amongst her Sisters, and the scenes amidst which she worked out her salvation, and, incidentally, her sanctification. There may be shadows as well as sunshine; there are both in every true picture. Only in heaven shall we have the true land where it is always afternoon.

In the Gospels themselves we have side by side the portrait of the wholly perfect Man-God, and the first apostate priest, his own friend. The visible presence of the Light of the world did not produce a shadowless picture. The cockle is to be allowed to grow with the wheat. Why should we pretend that there is no such thing as a weed? No matter how deep the shadows in any living picture, even before the end, the sunshine will creep in and absorb the darkness. Half-truths are nowhere so unconvincing as in a biography, and any attempt to paint a picture of even a short life, leaving out the shadow of the Cross, will surely be a failure.

Sister Marie Celeste, Marie-Jeanne van Eeckhoudt, was born on August 7, 1875, at Brussels, and found an elder sister Mathilde and an elder brother Jules waiting to receive her in the old house in the Rue Haute, where her parents had a large stationery business.

John Baptist van Eeckhoudt and his wife Catherine Kebers belonged to old and highly respected bourgeois families. Two of little Marie's maternal uncles were distinguished public servants; one was a well-known lawyer, and the other the director of customs, and during the world-war did good service for his country as Director-General of Finance. Several of her cousins have risen high in the professions of engineering and medicine. But above and beyond all worldly honour and advancement, Monsieur and Madame Eeckhoudt prized their century-old devotion and service to the Church, and their one desire was to see their children carrying on the same honourable traditions. In the bringing up of their young family Catherine seems to have stressed the sterner views of life, while we find the good-natured John Baptist, sometimes even surreptitiously, providing games and innocent amusements for the little ones, whose daily round included not a few pious exercises.

In his youth M. Van Eeckhoudt had dreamed dreams, which he confided to the good Curé, whose delight he was by the piety and the devotion with which he served at the altar, and between them they succeeded in getting permission for little John to begin studying art in the studio of a well-known painter. But alas! The death, within a short time of each other, of his protector and the artist shattered his dreams, and he was obliged to return to his father's house, and to take his place in the business which was to be his inheritance; but he never lost the debonair manner which he had acquired by his short-lived experience of a mild Bohemia.

Later on he loved to take his children out on Sundays or holidays, and to show them the many beautiful objects of art in Brussels, and to teach them how to know and love everything beautiful. To Mathilde and Jules all this was sheer joy, but little Marie did not share her father's tastes, and said frankly more than once, "Thank you, papa; I like much better staying with mamma."

The children might well have been spoiled if the calm, stolid figure of Madame had not been there to counteract any such tendency on the part of her husband. Not that she was a hard woman, far from it, but she did not know such a word as disobedience, and to her duty summed up each hour of the day. What she lacked in imagination and intellectual gifts she made up for in sound common sense.

We have only to look at the photograph of little Marie, aged eight, or, again, as we see her at twelve years old, to be able to analyse her mother's character to a nicety. Strong, sensible stuff clothes, made without a frill or furbelow; thick woolen stockings, and uncompromisingly solid lace boots; the hair drawn straight back from a wonderfully beautiful forehead - all proclaim the sensible, hard-working mother, who loved her children most sincerely, but had no time to spend on trimmings.

She was a woman of very deep feelings, and the love of her life was her little Marie; but she did not spoil her, and expected her to obey without demur, and when the little girl, as not infrequently happened, we are told, was inclined to sulk, her mother's surprised tone as she said, "Well, Marie, are you going to sulk over such a trifle?" soon brought the smiles back, and sunshine once more reigned.

Perhaps the person who brought most joy into the lives of the children at this time was the old grandmother, Madame Kebers; and it gives a very charming touch to the family picture to be told by Mathilde that Grandmamma always understood that Jules wanted plenty of space to kick his feet about in, even in the parlour, and would never allow him to be suppressed.

Madame van Eeckhoudt was, however, a little jealous of the children's love for the old lady, and if the visits were prolonged too much she sent to call them home, especially the little Marie, whom she could not bear out of her sight.

If their mother was somewhat austere in her views concerning their bringing up, she was the first to give the children the example of what she taught. Long before anyone else in the house was astir she was on her way to daily Mass, and only on her return did she wake her little ones, and hear them say their prayers.

The prayers were evidently said opposite a statue or picture of the Child Jesus crowned with flowers; for one of the three tells us that the first prayer they learned, and which have ever since recited, was, "Little Jesus, crowned with flowers, come into my heart and stay there."

Little Marie seems to have profited well by her mother's example and teaching. We are told that very early she began to make great efforts to overcome her naturally impetuous and quick temper, so that the outbursts became less frequent, and never degenerated into real quarrels with her sister and brother, who both loved her very much, and very soon began to give way before her more virile and decided character. It says much for the amiability of her nature that neither of them showed the least jealousy of the decided partiality shown by their mother for her.

Madame van Eeckhoudt early accustomed her children to take their part in all household duties, and encouraged them to make clothes for the poor and themselves, and even sent them occasionally to serve in the shop, in order to teach them good manners and politeness in dealing with others. But she did not encourage them to make friends outside their own family circle, and they visited no houses except those of their relations. Marie and her sister were sent to the excellent school kept by the Sisters of Charity, in the Rue de Poincon, and, in 1892, Marie passed with honours the Government examination in music, domestic economy, and free-hand drawing. Music was always her favourite study, and it was the delight of her father and old grandmother to hear her play or sing, for she had a really beautiful voice.

Study had never any attractions for her, and she often expressed her astonishment at the interest her sister found in books of travel, and, indeed, in all kinds of reading. She never had more than one prayer book, so that already, as a child, she was evidently drawn to the more contemplative way of prayer. She seems always to have been silent and reserved, somewhat of a dreamer we are told, but very amiable and thoughtful for others. The home in the Rue Haute seems to have been a very happy one, and though to modern children it would have been singularly devoid of amusements, perhaps the little van Eeckhoudts enjoyed the yearly treat of the Akermesse, or fair of Brussels all the more from its being such a rarity. Marie took her full share of riding on the roundabouts, and of the various other amusements.

So her happy childhood wore on, and her tenth year dawned, which was to bring with it one of the most important days of her life, her first Communion. Sister Mary Edward, the Mistress of School, set herself to prepare her dear "Mariekin" for this great event. Marie, on her side, redoubled her fervour by placing herself more particularly than ever under the protection of her heavenly Mother and her chosen protector, St Joseph.

With her admission into the class of first communicants, Marie set herself more earnestly than ever to correct her faults, especially her quick temper and her wilfulness, which it had always been the aim of her mother to overcome. When she was still a little child, her brother and sister experienced what one of them expressed naively: "When Marie says 'I will,' the thing must be done." Now, however, we find the little girl gaining more and more the mastery over herself, and winning the love and esteem both of her mistresses and her companions, so that she left a lasting impression on them of a singularly lovable and amiable character, always ready to give in to others and to help them in every way.

According to the prevailing custom in Belgium, Marie made her first Communion on Passion Sunday, April 11, 1886, in her parish church of Notre Dame de la Chapelle. Few details remain to us about this day, of which Marie later on said, "Oh! That was indeed a day of heaven for me."

One of the curates of the church, a very holy priest, said to Madame van Eeckhoudt: "Madame, your little Marie is a saint. When I saw her coming back from the Holy Table I could not take my eyes off her, for I have never seen such an expression on the face of a child. It was that of an angel adoring the Divine Majesty." It was perhaps at that moment that the little girl was listening to the call to follow the Lamb, which, we know from her own lips, resounded in her heart that day for the first time.

In spite of her great piety and eagerness in the performance of her religious exercises, Marie was not at all a goody-goody child. She loved games, and was the first at recreation to take the lead in any amusement, and entered into the spirit of them with her whole heart. What did astonish her companions was that she, who was the life and soul of the game, should on a sudden, at the first stroke of the bell, lay aside the ball, or other plaything, and become at once the staid little girl, whose one preoccupation in life seemed to be the stocking she was mending, or the exercise that had to be carefully written. Marie was already following in her mother's footsteps and learning to place duty before everything else. Even so early she had acquired the habit of knowing no hesitation when the call of obedience summoned her.

A short time after Marie's first Communion the happy home in the Rue Haute was visited by much trouble and anxiety. The business was rapidly declining, and in order to keep pace with the times a whole new plant would have to be introduced, an expense which the worthy proprietors could not face. There seemed nothing to be done but to give up the whole concern, and try and regain part of their losses in a much humbler way of business. It was with bitter sorrow that the poor mother faced the prospect of selling the home, in which all her married life had been spent, and where her dearly loved children had come to add fresh joy to her life. She shared her sorrow with her eldest daughter, Mathilde, then little more than a child herself, and together they wept and prayed. "Let us pray harder, mother," the girl said after one particularly trying day; "and we will get Marie to pray with us." Madame was almost beside herself at the thought that, young as they were, she might be forced to send her children out to earn their own livelihood, but at the mention of her dearly loved Marie her courage returned. She answered quickly, "No, no; say not a word to her; I forbid you; let her remain happy." All her mother's heart went out to shield the baby from too early a sorrow.

Happily, prayer succeeded when all human efforts had failed; an unexpected turn in the tide of fortune put the business again on its feet, and the happy life continued as before. Marie became more and more the sunbeam in the old house, and each day Madame van Eeckhoudt depended more and more on her, especially when, at the age of seventeen, she left the school, and took her place as her mother's right hand in all household affairs. For this she was well qualified, for she had gained her diploma, with honours, for domestic economy. It was in the year 1892 that Marie came home for good. Her mother's health was beginning to fail; doubtless she herself felt already the first beginnings of the fatal malady that was so soon to carry her off. Marie was all in all to her, but even she could not stay the progress of the dreadful cancer, and, in 1894, Madame van Eeckhoudt died after a painful operation, from which she never recovered.

Of a less virile and more emotional temperament than his wife, Monsieur van Eeckhoudt sank under the sorrow that made his house desolate, despite the love and affection of his children, whom he adored. He never seems to have recovered sufficient strength or courage to apply himself seriously to business again, and the home was more or less broken up. Jules entered another firm, and Marie went to live with her grandmother, Madame Kebers, and her two aunts who had a flourishing drapery house at the other side of Brussels.

Foreseeing her own death, and knowing what would then happen, Madame van Eeckhoudt had already sent Marie to learn business with these good ladies. She had acquired great proficiency in book-keeping and the management of affairs, but she came home every evening, and one of the few joys remaining to her relations was her music. As soon as the evening meal was finished, Marie seated herself at the piano, and the sound of her lovely voice, for some few hours at least, drove sorrow away from those she loved. At her mother's death, however, Marie went to live entirely at her grandmother's, only returning on Sundays to spend the day with her father and Mathilde.

To her aunts this arrangement was a sheer joy; their niece had become almost indispensable to them, and they welcomed her most cordially, as did her grandmother, whose favourite she had always been. To the young girl herself, however, it was a sad life; she felt keenly her mother's death and the separation from her father, feeling his sacrifice almost more than that entailed on herself. Above all, she missed the old quiet home life, where she had been accustomed to so much liberty for the performance of her religious duties, and where she was able to indulge her love of solitude and silence.

Now, of necessity, she was from morning till night in the shop, where her winning manners and bright happy smile attracted many customers, and the business increased wonderfully. The very way she bowed to acquaintances in the street made them eager to see her again, and many came to buy who were drawn there by the charm of the niece rather than by the goods of the aunts.

In order to secure her daily Mass and Communion, Marie had to rise very early, and a friend of those days tells us how each morning, sometimes even before daylight in winter, she used to see the young girl hurrying along to the Church of the Madeleine, either alone or accompanied by a servant with whom she had already been to the market for the household provisions. It was at the Madeleine that Marie first became acquainted with the Redemptorist Fathers, one of whom especially was to have so much influence on her and her future life.

Old Madame Kebers was nearly at the end of her long life, and Marie devoted herself particularly to cheering the lonely hours of the old lady and to mending her gloves, for it had become a joke in the family how she was continually wearing out her gloves. One day Marie said to her laughingly, "Grandmother, I know how you wear out so many gloves; it is because you are saying your rosary from morning till night, in the streets as well as the long time you stay in church." The grandmother flushed very red, saying, "Well, say nothing to the others; I will go on saying the Aves and pray for you, and do you go on stopping the holes."

To her grandmother also Marie's music was a great solace, as it was to an old aunt, a sister of Monsieur van Eeckhoudt's, whom she often visited. Though not really old, this aunt was quite blind, and her life was very desolate; the visits of her niece became her one joy, and she seemed to spend her whole time listening for Marie's step upon the stair.

In 1900 the second big sorrow of her life came to Marie; her father died. Though perhaps the void made by his loss was not so great as that when her mother was taken from her, yet she felt the loss keenly, and, as in the former case, her grief was all the more profound that it was the more undemonstrative.

Her sister tells us that up till now Marie had said little or nothing about her religious vocation, knowing how much pain her decision would cause her parents. On her declaring her intention at the time of her mother's death, her aunts had vigorously combated the suggestion and she had much to suffer in consequence.

Still more alone when the house in the Rue Haute was finally given up, she again made known her intention, and her resolution was backed by the authority of her director, Father Strybol, C.SS.R., who stood high in the opinion of all Brussels for his sanctity and rectitude of judgement. All was to no purpose, and Marie had still many a bad quarter of an hour to pass through before she could spread her wings and fly away to the desert.

In 1899 Mathilde van Eeckhoudt married, and not long after her brother-in-law wished to make the ties between the two families still stronger by himself marrying Marie, and for this purpose he sought the mediation of her sister; but more forcibly than ever she declared her intention of never having any other spouse than a Heavenly one. She waited and prayed, and showed her aunts more deference and amiability than ever, and at last even they became convinced that it was useless any longer to thwart her desires. Yet it was not without much pain and many regrets that they at last gave way before the persuasion of Marie's director, and gave their consent to the niece's entering a convent.

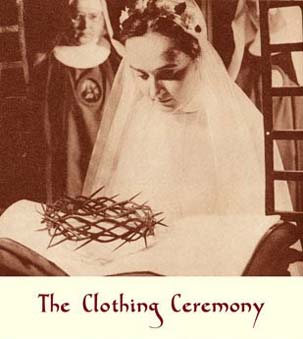

Unknown to them, she had already four years previously paid a hurried visit to the home of her choice; this was the convent of the Redemptoristines at Malines. A friend of Marie's tells us that she had for some years marked her separation from the world by dressing herself like a servant. This can have been no small mortification for a young, sensitive girl in a stylish capital like Brussels.

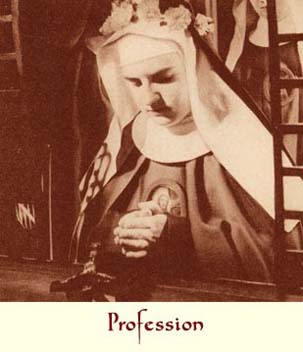

At last, on February 18, 1900, Marie, accompanied by her Aunt Bertha, set out for the promised land, where two other young ladies were to join her and together start on the road of religious life. So great was the young girl's joy at arriving at her destination that her aunt was quite overcome at the thought of how by every means, gentle and otherwise, they had tried to hinder the achievement of this object. "Oh, Marie!" she exclaimed, "we did behave badly; if I had to live this time again I would behave very differently."

Marie always entertained great affection for her aunts, especially Mlle. Bertha, and never, even to the one who was the confidante of her most intimate thoughts, did she ever complain or cast any reflection on the two ladies. †