A Vocation – Marie de Courtebourne [1]

It is a beautiful and gracious history of this young girl of the great world. Vowed since her birth to Saint Louis Gonzaga by her devout mother, Marie de Courtebourne grew up in innocence. She knew of the world only to appreciate its vanity. She opened her entire soul to the sweet influences of piety, and finished by embracing the religious life.

Are we to follow her in the different stages of her short existence? No. We shall see our humble heroine neither in Ghent where she was born, nor in Oostacker, [2], nor in Rome, nor in Assisi, nor even at Malines where she became Redemptoristine nun. We shall content ourselves to some degree by drawing the moral portrait of this beautiful soul, while borrowing from her the traits under which she was painted unbeknown to her.

I. –In the World.

One day Marie de Courtebourne opened a publication used by her father. Her pious mother arrived in the meantime. Fearing that her daughter's eyes would fall on dangerous pages, she took it away from her forcibly. – “O my mother,” the young girl said later while remembering this circumstance, “what a service you rendered me by forbidding me to read anything without your permission!” – “Yes, the scene in that room,” replied her mother; “I remember it now. I was too stern, my child.” – “It was the only time you spoke to me severely,” replied Marie, “and you were right a thousand times. I never forgot the way you looked at me. It impressed me even more than your words. You appeared so angry that I thought: “Such reading must be very dangerous for me, since mother seems so alarmed”, and every time since then that I have been tempted to read something, I remember what you told me, and it prevented me from succumbing. I never disobeyed your prohibition.”

The pious child read “The Imitation of Jesus Christ” assiduously. She also had a tender devotion to the Blessed Virgin. “I love the Virgin Mary very much,” she told her cousin, Marguerite of Limbourg, one day. She is a tender mother to me, and I love to call myself her child. But imagine how unhappy I am. I have tried in vain, but I do not have the same devotion to my guardian angel, as my aunt Matilda had.”[3]

In her quality as an older sister, she initiated her young friend into the practices of the spiritual life. One day, she taught her to make a private examination, and she was very sincerely humbled in scarcely knowing how to succeed in it herself. “As for me,” she said, “I have a great deal of trouble in doing it, so I never manage to correct myself of my defects, and I always have my dominant defect warring against me.” –“You?” replied her little cousin. “But what defect do you have then? I don't know of any dominant defect in you.” – “I have too much human respect,” replied Marie. – “It would not have come to anyone’s mind,” says her historian, “to assign this defect to her, so much did her oneness with the Church excluded any preoccupation of this kind! She prayed with a childlike simplicity, speaking to Our Lord at all hours of the day and night, and confiding to Him with a supreme abandonment all her joys, troubles and desires. Her prayers were both naive and fervent. It was the ingenuous language of a heart that goes in all confidence to Jesus.”

Even when very young, Marie de Courtebourne loved the poor. One morning, her father gave her a beautiful new shiny coin as a reward. The child looked at it and had everybody admire it. In the evening, a poor man came by. Marie ran back hurriedly into the castle. “Where are you running to, Marie?” her grandmother asked her. –“To find my new coin to give it to this poor man!” And she wanted to put it herself into the poor man’s hands.

A little later, she felt an irresistible attraction for the religious life. “If I enter the convent”, she wrote to her director one day, “It would not be to live a tranquil life. I have already seen enough religious houses to know that all the human miseries are found there. Characters are more or less soured by the common life, the austerities, the monotony of the places and the occupations. I do not want to delude myself. There they will treat me like a useless piece of furniture, a burden on the community. I will be tormented and harassed by the confessors, who will want to make me advance in perfection, and the demon will not let me alone. Even the good God will hide from me very often and He will send me trials, or rather His caresses of love.

“I would like my life to be a continual sacrifice, a continual act of love. I would like to have no more liberty, to obey blindly, and give myself to the good God as much as we can give ourselves here below. I would do anything for this.”

But her father? And the wonderful husband that would be offered to her? – She replied: “I am just as astonished as you at my idea and this stubbornness in wanting to shut myself within four walls in, bringing pain to my family, and having everyone against me, when I am so feeble and timid. Humanly speaking, it would be better to lead happy life, see the world, and contract the wonderful marriage that my father spoke to me about at Assisi, with one of the best suitors in France. I replied to my dear father that I was still very young and that we would think about it later. In the depths of my heart, I told myself that the good Jesus would call me to Himself, either in heaven, or in the convent.”

She marvellously understood the price of religious obedience: “The whole life of Our Lord,” she wrote, “was but a succession of afflictions and privations. I would not really have had the moral strength to enjoy my liberty all my life. The good Jesus was obedient unto death, and to death on the cross! In the world, perfect obedience is impossible, even less to be renowned for it. You cannot always run after your confessor, nor live in hermit, especially in my position.”

Finally, her attraction to the life of privations became irresistible: “My desire for the religious life,” she wrote to her director, “is always increasing. It is costing me to live in abundance, while poor Jesus suffered so much. I would like to be hidden, and forgotten, and have no more liberty. But above all I want to do the will of God.” – “My attraction,” she added, “is for the Order of the Redemptoristines, founded by Saint Alphonsus of Liguori. I very much like its spirit of abnegation and detachment. – No, my Father, I am leaving everything or rather nothing, in order to find everything. Even if I was the daughter of a king and had a million dollars to spend every day, I would not hesitate, with the grace of God, to become a religious.”

II. –In the Cloister.

Such admirable sentiments were to lead Marie de Courtebourne to the port she desired. She entered it in 1878. Of the convent of the Redemptoristines of Malines she wrote after fifteen days: “I did not believe that my happiness would be so great. You would not recognize me. I am usually sleepy and shy, but now I am extraordinarily lively, my sight alone makes even the most serious Sisters laugh and I prattle on like a little magpie. Everyone is very good to me. I am the youngest of all. I have no trouble following the community exercises. You would think I have always been doing them!

“I am so happy to sleep on straw!” she wrote another day. “In the world, I had too soft a bed, and I cried with frustration at seeing myself so mollycoddles, while the good Jesus had so much to suffer.” “She asked,” said her historian, “to continue the mortifications that she did at home: to choose the dishes that most repelled her, depriving herself of seasonings, and using other little industries dear to Christian penance. She added: “I have suffered enough from living in abundance, having everything I could wish for, and resembling the poor and suffering Jesus so little. I always wanted to be poor and suffer to give pleasure to the good God.”

She told the Mistress of Educandes one day: “I did not know that you could love the good Jesus so much. I have not yet told you how I learned this. I was about sixteen years old. One day when I had just received communion, I believed I heard a voice immediately afterwards telling me: “Love me.” – I was afraid and I did not dare to say anything. At the following communion, I heard the same words again. Then I was really afraid, and I said: “If it is You speaking to me, O my good Jesus, tell me what I must do to love You. I am so lowly! I know nothing. – Then I understood that the good Jesus would Himself teach me to love Him, and that love consists in suffering.”

In the convent, she had no human respect. “In recreation,” one of her companions tells us, “And at table when she was permitted to speak to us, she often told the Sister beside her: “Let us speak of Jesus. Tell me something about Jesus. Let both of us really, really love Jesus, because everything consists of love, in loving only Jesus.”

She had a little old crucifix made of copper that she kept carefully before her, on her table, or that she carried with her. How many times she was surprised kissing it! And she would say: “You don’t need to have beautiful Christ's to love Our Lord. In this manner at least you can always have one with you.”

Her humility was sincere. “I am very arrogant,” she told her Mistress during her first days. “When you know me better, you will see how much self-esteem I have. However, here I am reassured, because I think you will always warn me when I don't act well. I don't dare count on myself. I have so much arrogance!”

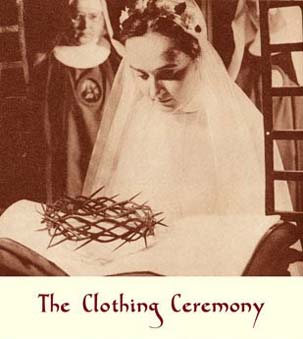

On June 5, 1879 the vesting ceremony filled the pious young girl with joy. She was happy to receive the name of Sister Marie-Aloyse of the Crucifix, which united her favourite devotions so well and reminded her constantly of her poor and crucified Jesus Christ, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the angelic Saint Louis of Gonzaga to which her mother had dedicated her since her birth.

One of the most agreeable features of religious life and one of the most recommended by the masters of spiritual life, is simplicity. Sister Marie-Aloyse of the Crucifix was of this character. “She read but little” says her historian, “and only the simplest books, especially those of Saint Alphonsus, attracted her preferences. She told us more than once, that one of the motives that had made her choose the Order of the Redemptoristines was the simplicity that distinguished the spirit of the holy founder. During her days of retirement, it was sufficient for her, outside the prescribed readings, to have her crucifix close to her, and to look at it and converse with “her good Jesus,” as she said piously. This expression was familiar to her, and she repeated it with such an accent of sincerity and fervour, that these words alone revealed all her soul. Yet it was not only the name of Jesus that she liked to savour; communion had for this naive soul its ineffable delights. Through the Eucharist she experienced those mysterious attractions known by in which Our Lord maintains the precious grace of infancy. When the Blessed Sacrament was exposed, she could not do her hour of adoration without pouring out abundant tears, and it was a profound edification for her young companions, when they happened to surprise her in this state that recalled the touching piety of her aunt Mathilde.”

Her love for work was no less remarkable. Sister Marie-Aloyse forgot what she once was, what she could have been, and took the apron and the broom, and indistinguishable in the ranks of the other beginners, red with pain and beaming with joy, washed, swept, dusted, polished furniture, and stopped only when the task was finished. If there was linen to mend, she asks that her part of this work be what was least pleasant, the coarse and worn-out stockings, the aprons made of grey canvas, and she said merrily: “I had so much pleasure in mending this old stocking!”

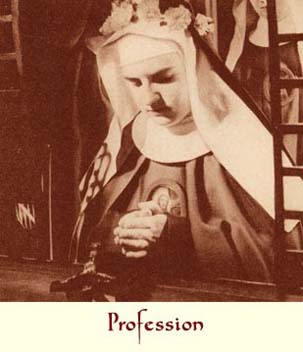

On June 10, 1880, the fervent Novice was admitted to religious profession. She then wrote the following lines to her grandmother, the Marchioness de Courtebourne:

“It would be impossible for me to express to you exactly the happiness, peace and sweetness I felt after pronouncing my holy vows. You would have said that I was in heaven. I also felt my good parents blessing me from the highest heaven, and were rejoicing in my happiness. How short the time seemed to me! I am going to have a provision of the love of God and patience for all my life, during the first beautiful days of marriage, the honeymoon, as we say in the world, in order to well prepare myself for everything that the divine Spouse will ask of me later on.”

The good Sister Marie-Aloyse had something of a presentiment of the troubles that were going to pour down on her, and the trials that she had to pass through. While she is waiting, let us listen to her once more. She had embraced the common life of the Professed Sisters and she was given a task. “On the first days,” she wrote, “I was a little out of my element, but now I have learned what to do. I have been nominated as assistant housekeeper, under the orders of the good Sister who takes care of the provisions, the housekeeping and work to distribute to the Converse Sisters. It amuses me a lot to trot around in a white apron and to prepare what is necessary for the Sisters. You would be pleased, I am sure, to see me in my new task.”

What most pleased Sister Marie-Aloyse in the functions that were entrusted to her, was not so much the novelty and the picturesque nature of the costume, but rather the opportunity to spread around her the charity overflowing from her heart. Her happiness lay in giving pleasure to others while sacrificing herself. With the gentleness that only charity can inspire, she knew how to render service, give comfort and console, while accommodating herself to all characters and differences in education. When the appointed housekeeper was indisposed, the young Sister was obliged to provide for everyone by herself, and in the exercise of her functions, she distinguished herself her tact, her judgment, and her spirit of poverty.

We shall not speak here of the interior trials of Sister Marie-Aloyse of the Crucifix: we refer the reader to the beautiful book by Abbé Laplace. Nevertheless we shall quote one of her letters before we finish. She was suffering from a chest illness that would not diminish. Novenas followed novenas, and brought only an increase of suffering. However the patient was always cheerful, resigned and happy. She wrote to her maid-servant, with whom she had remained in correspondence.

“I can take several steps with the help of a charitable arm. But I don't have the time to be bored, my dear Pélagie. I am occupied very peacefully, and I tell you to amuse you, that I have become an artist in mending stockings. My whole pleasure is in mending big holes. I pray, I read, I write and the days pass very quickly. Also I often have a few hearty laughs, as in the convent we are never sad. On the contrary, the service of the good Jesus cheers up our hearts, which are, if not always joyful, at least are always calm and tranquil. If I told you that I am the happiest creature in the world, even without being able to walk, you would not believe me, and yet it is the truth. True happiness consists in fulfilling the will of God. So long as He is happy, what does the rest matter?

It was with this holy joy that Sister Marie-Aloyse bore her painful illness. How many interesting details could we still mention! But we must limit ourselves. 25th August 1884 was the day of her supreme sacrifice. The fervent nun received the last sacraments with the most tender piety. Then she collapsed, but without losing anything of her presence of mind, or the lucidity of her intelligence. “Now I understand everything,” she repeated, “I understand everything!” When the Reverend Mother approached her bed with the Infirmarian, she asked her if she recognized them. “There is only God,” she replied. They were her last words. It had been her motto all her life..”

Footnotes

[1] See the charming biography called A Vocation. – Marie de Courtebourne, by Abbé Laplace, the Superior of the Institute of Saint Peter at Bourg (1 vol. in-18, Lecoffre, Paris ;) Vandenbroeck, Brussels; Vitte and Perrusel, Lyon.

[2] t was in the castle of Oostacker that the famous Derudder was a servant. His miraculous cure has been very well recounted by Father Bertrin in his beautiful book : Lourdes, Apparitions and Cures.

[3] Miss Matilda (Mathilde) de Nédonchel, deceased at Rome in an odour of sanctity on 27th June 1867, at the age of 24. Her Life was written by Abbé Laplace. (1 vol. in-8°. – Casterman, at Tournai).

This necrology is translated from Fleurs de l'Institut des Rédemptoristines by Mr John R. Bradbury. The copyright of this translation is the property of the Redemptoristine Nuns of Maitland, Australia. The integral version of the translated book will be posted here as the necrologies appear.