Born Philomena Huben

The life of Sister Marie-Innocentia was a short one, and the account of her actions can be told in just a few pages, but it contains so many edifying and charming features that we wish to recount it for the good of our Sisters and our future Sisters. [1]

Sœur Marie-Innocentia was born at Munster-Geleen, a village in Dutch Limburg on 24th October 1847, and received the names of Marie Catherine Philomena at baptism. She was the only child of Mr. John Peter Huben, a property owner, and Anna Catherine Donners, who died several weeks after bringing her to the light of day. At the age of seven she lost her father. Some close relatives then confided her education to the Ursulines of Sittard. The very pure heart of the little Philomena thus opened more and more to piety and virtue, and moreover, these were a family inheritance. Two of her uncles were consecrated to God. One was a secular priest and the other died in Ireland in 1893 in an odour of sanctity. He was Father Charles of Saint Andrew, a Passionist.

At the Ursuline Convent, the child was distinguished by her horror of sin, her filial obedience and her friendliness to her companions, and so she was loved and esteemed by all. She remained in the boarding-school until she was fourteen and then lived with her uncle and her two aunts, his sisters. And it was there that she remained until her entry into the convent, on 9th September 1865. She spent only a short time in the world. God gave her the grace of understanding that the world was not without its dangers for her, and even during her years in the boarding-school, He gently attracted her to religious life. Having heard a Redemptorist Father, in the course of a retreat, speak of the Order of the Redemptoristines, she felt herself strongly drawn towards our Congregation, but her attraction was to be keenly challenged.

Having fallen dangerously ill, she thought more than ever of her plan, but her near relatives and the doctor strongly urged her to renounce it. So then she lost all attraction for religious life, but this distaste seemed suspect to her. She wrote to her director, Rev. Father Vanderlinden, and explained the state of her soul to him. The pious Redemptorist did not have much trouble in showing her that she was under the attack of a temptation. He reminded her how he had approved her vocation, forbade her to speak to her doctor on her own, and recommended her to follow God’s call as soon as possible. She followed this advice to the letter.

* * * * *

Presented to the Superior of the Convent of Wittem by Father Vanderlinden himself, Philomena was accepted and entered the monastery a short time later. The prejudices that her doctor had inspired in her against the lack of charity which he said reigned in the convents, and against the lack of care that they gave to the sick, these prejudices, as we call them, soon disappeared. In fact she saw quite the opposite. She loved our house and our community as if she had been born there, and this contentment was only to grow to the degree that she discovered the treasures enclosed in the religious vocation, and so she would speak of this with enthusiasm.

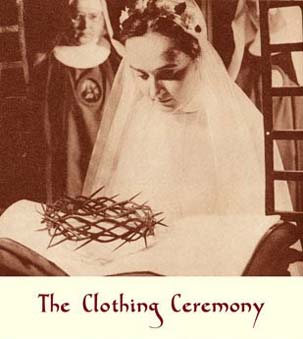

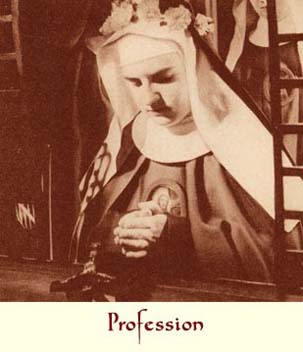

From the very beginning of her new life, she recognized her faults and fought against them firmly. She understood that if she had been until then a somewhat spoiled child, she would now have to cut all caprice short and immolate her will, and she did so ardently. Her delicate constitution hardly permitted her any great austerities, so she turned more and more to obedience, which is the martyrdom of the soul. When she took the veil, which happened on 27th September 1866, she received the name, so well chosen for her, of Sister Marie Innocentia of the Holy Family. She took her vows a little later.

Beginning with her taking the veil, our dear Sister had only one desire, and pursued only one end, that of advancing in perfection. One could say that she had a presentiment of the little time that she was still to live, as she was a true spiritual miser, wishing to amass the treasures of merits, and as she had a real hunger and thirst for justice, she was filled, according to Our Lord’s promise.

A great perception about spiritual ways, a perfect obedience, a veritable passion for obliging everyone, but for the love of Jesus Christ, and finally, a sincere humility – these were the characteristics of the life of Sister Marie-Innocentia.

The things of God accorded well with her soul, and so she desired them keenly. Teaching, spiritual books and pious discussions found a well prepared soil in her heart, and it produced abundant fruit. And her delicacy of conscience led her to becoming entirely faithful to God, and we may say that she never committed a voluntary fault against the Rule. This delicacy, towards the end of her life, was even a source of scruples and anguish for her, but even though they harmed her health, her pains and struggles did not make her either sad or melancholy. She obeyed, and it was an edifying spectacle to see her, on certain days of communion, approaching her Superior to explain her doubts to her, and then at a simple sign from her, approach the holy table with the docility of a lamb.

Marie-Innocentia faithfully followed the inspirations of grace. From then on she observed even the least prescriptions of the Rule and even anticipated the wishes of her Superiors. If she heard the ringing of the bell, she flew, if that is the word for it, to the place where it called her. The Angelus caused her to abandon every occupation. She could be seen falling down on her knees while she washed her hands, and reciting the holy prayer before wiping them. She never permitted herself the least reply to her Superiors, and, what is even rarer, she willingly obeyed her subordinate Superiors, even the converse Sisters in the exercise of their charge. Had she not written: “I wish to obey everybody.”? However, she did it with wisdom. When a converse Sister said to her one day that she needed to take a tonic, she went looking for the Mother Superior everywhere in order to obtain the necessary permission.

Her zeal to oblige everyone was not inferior to her obedience. Because of the feebleness of her constitution (as from her childhood she suffered from horrible liver colics), she could not be assigned a particular function, so she took on, if we may so call it, the function of obliger general. And this is how, until her death, she had the task of going into the garden and gathering the different leaves used in making herbal tea. Later on, as an assistant infirmarian, she dried and arranged herbs with the patience of a professional herbalist. As she was not able to hang out the washing, she would at least clean the lines the clothes hung on. The stockings of the Choir Sisters, and those of the Converse Sisters, were all mended carefully by her hands. In the refectory or during the afternoon work, she became the Reader, and on Sundays and feast days and other days as well, she would wash the dishes. In a word, through a thousand little services, either general or particular, she made herself very useful to the community, and the good humour with which she did everything made this service even more valuable.

Her humility appeared in joyfully accomplishing the most insignificant occupations. She lacked the strength for large works, and fine work was forbidden to her, both because her hands sweated and because of the feebleness of her eyes, which she had to preserve because of the Offices. She submitted herself entirely to the will of God and accepted all her incapacities. She was even cheerful when the Mother Superior sometimes laughed at her and said: “After all, you are only a poor unfortunate!” In a word, her conviction on the subject of her incapacity was total, and she was singularly astonished when she was named as Auditrix, [2] as the Rule required a great deal of intelligence and tact for this function. However, she was not as deprived as one might have thought. She spoke and wrote three languages – Dutch, her native language, German and French.

This sincere humility and complete disengagement of herself also appeared in the letters that she sometimes wrote to her close relatives. We especially recall the memory of a letter that she addressed to Mons. the Archbishop Paredis to explain some temporal matters to him. She told him in a truly touching simplicity about her few means and her feeble capacities. In a word, she sought to humble herself in everything. During her retreat for her profession in 1868, she wrote: “From now on, I wish to practise the holy virtue of humility in words, thoughts and actions, and I wish to fight my sensitivities and apply my particular examination to this point.” To effectively keep such a resolution requires a rare virtue. In praise of Sister Innocentia, we may say that she was perfectly faithful in it. In fact, she was never observed as being hurt by any observation, and the shadow of discontent was never seen to appear on her face. If she was contradicted or corrected, she would say calmly and sweetly: “You are right. It is true”, or else she would ask pardon and promise to correct herself. One day, in recreation, she happened to mention the writings of the blessed Henri Suso, whom she loved to read. She said: “I always wish to be the cloth which the Blessed speaks of.” [3] So she let herself be guided and corrected without ever resisting. And may we add to that an extreme delicacy of charity indeed, and then we will have a good idea of her virtue.

Her uprightness of intention was no less remarkable. “I have given my heart entirely to my Saviour,” she wrote, “and I wish to seek nothing other than His holy will. I wish to seek God alone and please only Him.” This elevated and supernatural view singularly highlights the virtues we have spoken of. Her respect towards her Superiors, her kindness towards her fellow Sisters, her attention to judging no one – all this was inspired by supernatural motives, and her life, which in appearance was so little increased with all the beauty of the divine love that inspired it. One day she had sewn some bibs for a sick Sister. She gave them to the Infirmarian who told her the invalid would be very grateful for them. Sister Innocentia replied: “I have not made them so much for her as to warm the heart of the Saviour.” So she always had God in mind. If she visited the sick Sisters, which she did willingly and frequently, she always spoke to them of edifying things, and told them about conferences that she had attended. In recreation, too, she would speak about spiritual subjects, and we would often admire the profound meaning of her questions and replies. So she spread around her, without any doubt, the good odour of her virtues, as the humble violet spreads its perfume around itself. Everyone cherished her, everyone sought to be edified by her, and in the community, all the Sisters had their eyes turned towards this “beloved child” of the house, who dreamed only of becoming forgotten, but whom the Lord loved to raise up.

* * * * *

To a great simplicity, Sister Marie-Innocentia added a gravity beyond her age and a modesty that inspired respect. The source of it was her continual union with God.

Always recollected in God, she would have believed herself to have committed an infidelity or a fault if, even in recreation, she had in some way taken her thoughts away from her Beloved. Day and night, we might say, she was occupied with the Child Jesus, and following the example of the Venerable Marguerite of the Blessed Sacrament, she honoured Him at every hour with a special homage. It was a great joy for her when she got up at midnight, the hour when the Saviour was born. She also had a very special devotion to the holy house of Nazareth, and would plunge herself into the meditation of the great miracles of love and mercy which happened there.

How could she not have been devoted to the Blessed Virgin? It was to this divine Mother that she had recourse with all her heart in her trials and pains. She would kneel down willingly before the image of Our Lady of Good Counsel and would say, after the example of our Father Saint Alphonsus: “Mary, give me always good counsel.” She loved to say her rosary before Terce: “This is how I assure myself,” she would say, “of the protection of the Blessed Virgin for the whole day.”

Her love of prayer was truly prodigious. When she prayed, she seemed to have forgotten about everything. With her eyes closed, she was completely absorbed in prayer, and if anyone came in then to speak to her, she would experience a seizure as if she had been torn away from a deep sleep. How great was her devotion when she approached the tribunal of Penance and the holy Table! One day someone spoke to her about the six “Our Fathers” that she usually said after the holy Mass to gain the Indulgence. “The time of thanksgiving is so precious to me,” she replied, “that I can do nothing else than to cling to Jesus and love Him. I recite the “Our Fathers” afterwards.

This pious soul was in love with solitude and silence.

While still a child she loved to be alone and often passed entire hours in solitude. So she always felt very happy when she was cut off completely from the world. She had little love for visits from her close relatives. She either prevented them or diminished their number. One of her letters addressed a few days before her death to the Superior of the Ursulines of Sittard, clearly shows us her love of retreat. Here it is:

“Very Reverend Mother,

“You will no doubt have a certain astonishment in receiving a letter from me, who has already spent several years in religion without giving you my news. Our Reverend Mother Superior has offered me the occasion. It is in her name that I have come to ask you to be good enough to have the attached little cords of Saint Joseph blessed. Would you please send them back to us by post, and we will cover the cost of sending them.

“Oh, my Reverend Mother, how happy I am, and how I thank God for my holy vocation! Here I am in solitude. I neither see nor hear anything of the world. I have only one care, that of my perfection, my sanctification. Every day I beg Our Lord to give me the strength and courage to work on this sanctification, in spite of my sickly state. I hope, sustained by so many means, the Office, three meditations a day, and many communions – I hope, I say, to attain my end. Have the charity, I pray you, to remember me in your good prayers, especially before the little Jesus, my divine Brother.

“Our Reverend Mother Superior and all the Sisters send you their very best greetings. They have asked me to write you these lines because I knew you beforehand. I greet you very respectfully, and also the Mother Assistant. May she be kind enough to recommend me to the Blessed Virgin, as I am doing for her.

“In the Holy Hearts of Jesus and Mary,

Your Sister in Jesus,

Sister Marie-Innocentia of the Holy Family.

Convent of Marienthal

5th September 1870.”

One can see from these lines how the good Sister ardently pursued her last end, that is to say, the perfect union of her soul with God in time and eternity. Her keen desire for heaven is easily explained from then on. One day they told her about the death of a Sister younger than herself. “How happy she is to die so young!” was her reply. She willingly watched over dying Sisters, and they heard her say more than once: “Oh, how wonderful their fate is! How much I too would like to die soon. I hope that my little Brother Jesus will not leave me for too long on this earth!” She had a premonition about her premature death. “I shall die soon,” she said one day, “as it is impossible for me to live a long time. I just long to die and go to see my Jesus!” A year before her death, they asked her one day, during recreation, what book she was reading. “The Eternal Truths by Saint Alphonsus,” she replied. “But you have known about them for a long time!” they told her. “Oh!” she replied, “one never knows when the Lord will come.” The pious child always lived in the spirit of the other world. “How much I love,” she said sometimes, “how much I love to hear the sound of a storm! It makes me think of the Last Judgement.” Sometimes too, she would say to the Reverend Mother and the Sisters with a sweet assurance: “No, no, I shall not live for too long. My little boys will not leave me for too long down here.” This is what she called the Holy Innocents with a charming familiarity, those heavenly friends for whom she always had a very special devotion.

* * * * *

Her ardent desire was accomplished. Her “little boys” came to seek her for the heavenly homeland sooner than we thought. Her frequent sorrows led her to gain many merits, and the patience with which she bore them greatly edified the community. Sometimes the crises lasted several days, during which time she could not take any food. She rejected everything, and it was almost impossible for her to have even a moment’s sleep. The Mistress of Novices told her one day that she should not always move around as she was doing, and she tried hard to obey her, but the violence of the crisis made her forget all about it, and then she was greatly saddened, believing that she had failed in obedience. In spite of everything she remained at peace and submissive to the holy will of God. Her lively faith showed her that her sufferings were a special occasion to show God her love. At the same time, she showed the greatest gratitude to the Sisters who were giving her their care.

However, death was approaching. Some months of respite were simply a halt before her final rest. On 16th September 1870 (it was the Friday before the feast of Our Lady of the Seven sorrows), Sister Marie-Innocentia was struck down by her previous illness. In the morning, she went up to the sacred table with all the Sisters, not thinking that this communion was to be her last. In the course of the afternoon, her pains began again, and the doctor declared that he feared a fatal outcome.

The feast of the Seven Sorrows was truly a feast of sorrows for the poor invalid. Because of her continual vomiting, she had to be deprived of holy communion, and what a privation in the midst of such horrible suffering! “My Jesus,” she kept repeating, “give me patience.” To such a sorrowful day an even more sorrowful night followed. The Sister who was caring for her told us: “She did not have a moment’s rest; she was constantly upright in her bed, with her hands behind her back, and leaning against the wall, and from time to time she said: “The Saviour was in this position in His dungeon, [4] and this thought gives me some comfort.” Soon the symptoms became more and more alarming, and all hope was lost. They went to find Rev. Father Van der Linden, and she told him with a touching sincerity: “Laetatus sum in his quae dicta sunt mihi; in domum Domini ibimus.” * - Turning to her Superior and her Sisters: “Reverend Mother and dear Sisters,” she asked them, “help me to suffer patiently.” She asked for her picture of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour, and pressed it to her heart. But in this very simple act, she had, by first kissing the hand of her Superior, and then the picture, observed her Rule to the letter. This is how she wished to die under the protection of Her who, during her whole life, had been, after Jesus, her sweetest consolation. However, Rev. Father Van der Linden still hesitated: “Come now, Reverend Father”, she said to him, “do not leave me to die without the sacraments.” Straight away she received a last absolution and Extreme Unction. Immediately afterwards, she died without agony, and her innocent soul flew up into the bosom of her Creator. This was at six o’clock in the morning. Sister Marie-Innocentia was aged twenty four, and in the third year of her profession.

All the Sisters wept because of the unexpected loss that they had just had. Father Van der Linden could not prevent himself from shedding tears, and as he left the enclosure he said: “Our young and holy little sister is already dead.” He immediately offered the holy sacrifice for her soul.

For several days the body was laid out at the grille and the public was admitted to pray before the deceased. From morning to evening the crowd did not cease to render her this last homage. After the funeral service the body of this dear little Sister was placed in the Convent’s vault. Everyone proclaimed her blessed and said: “She lived a long career in just a short time. Soon she will be reunited forever with her divine Spouse and will contemplate God in His glory.” The Mother Superior said: “I think I can already see our Sister Innocentia entering Paradise, followed by “her little boys.””

Many of our Sisters have addressed themselves to Sister Innocentia and successfully invoked her intercession. Her virtues, her good examples, and above all her innocence, obedience and punctuality, are still the object of our conversations. May we, after imitating her here on earth, one day go and rejoin her in heaven!..

Footnotes

[1] Extract from the Monastery Chronicle

[2] The name of Auditrix is given to the Sister charged with sitting in the background and attending interviews at the grille.

[3] Blessed Suso, preoccupied with the pains that awaited him, heard a voice telling him one day: “Open the window, look out and learn.” He opened it and at the entrance to the convent he saw a dog which had a tattered piece of cloth in its jaws. The animal was playing with the rag, throwing it in the air, catching it, biting it, and tearing it into pieces with its paws and claws. Brother Henri then groaned profoundly, and a voice told him: “This is how you will be torn one day by wicked tongues.” Then the Blessed thought: “may my soul trust in God and suffer without complaining like this piece of cloth!”

[4] The dungeon in which, according to some authors, Our Lord was thrown after His flagellation, and which Catherine Emmerich has so admirably described.

* Ps. 121: “I rejoiced in the things that were said to me: We shall go into the house of the Lord.”

This necrology is translated from Fleurs de l'Institut des Rédemptoristines by Mr John R. Bradbury. The copyright of this translation is the property of the Redemptoristine Nuns of Maitland, Australia. The integral version of the translated book will be posted here as the necrologies appear.