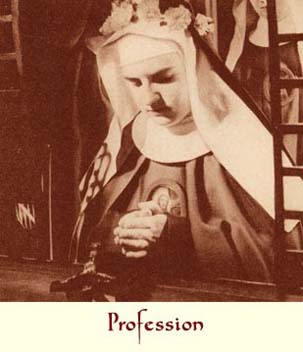

Foundress of the Convent of the Redemptoristines of Velp, near Grave, founded in 1858

Chapter III. Expulsion.

The year 1848 was to go down in the history of Europe. In February, revolution broke out in Paris. King Louis-Philippe had to flee in all haste, and some days later, the other thrones of Europe were also shaken. Austria was not spared. The city of Vienna especially was the scene of plunder and cruel persecution. For several days, the lives of the best citizens were exposed to the greatest danger. Priests and religious were exposed to the most brutal and ignoble pursuit.

To obtain an idea of the situation in the capital, it will be interesting to hear the accounts given by the newspapers and eye witnesses.

“In Vienna, the revolutionary mob set to work at the beginning of March. One morning, on 13th of this month, the rioters invaded the convent of the Redemptorist Fathers and ransacked it. The priests were forced to leave their house, put off their religious habit and put on lay clothes, and hide in the houses of some of their devoted friends. The Redemptoristines equally had to take shelter in some nearby houses.

“The weakness of the government had let everything take its course, and submitted without saying a word to the first demands of the revolutionaries. Calm was re-established for a moment in the city. It was concluded that the peril had been averted, so the Fathers and Sisters believed, in spite of the wise advice of their friends, that it was now possible to remain in their convents. This was on 30th March.

“But now on 6th April, in the morning, a troop of armed men made up of students and national guards invaded the Redemptorist convent, and roused up the furious crowd to believe that the priests did not deserve to remain any longer in Vienna. Some carriages were brought along and the Fathers were forced to get into them, and without being able to bring any of their things with them, they were driven outside the city. Rev. Father Passerat, their worthy Superior, an old man of 76, was so upset by this ignoble treatment that he lost his strength and fell when getting out of the carriage. These barbarians left him in the middle of the open country without paying the least attention to him.

“When the assault on the Redemptorist house had come to an end, the rioters now cried: ‘It’s the turn of the Sisters in Rennweg Street.’ And so their house was attacked on the evening of the same day, 6th April. At that moment, a large number of pious persons were in the chapel to attend benediction. The savage crowd which that morning had invaded the Fathers’ convent now invaded the nuns’ chapel. The chaplain was already at the altar, but these scoundrels would not permit him to begin the ceremony.

“The good Sisters were terrified and fled into their garden. The rabble had scarcely entered the convent when they gave free rein to their sacrilegious rage. Their impiety even went so far as to wrench a crucifix from the wall and trample it underfoot. They had carriages brought up and conducted the Sisters out of the city.

“A young revolutionary came up to one of these carriages, and noticing four religious in it, he spat at them as a sign of his profound contempt.

“Once outside the city, the Sisters were made to get out and they were left to go where they would. And so, as night fell, there were now thirty poor women, most of them very aged, who had been chased out of their house and forced to seek shelter in the darkness with whoever took compassion on them.

“Some of the Sisters, however, when the revolutionaries arrived, had found refuge with a neighbour, Mr. Goham, a tanner by profession, whose house adjoined the Monastery garden. This generous man declared that he would never permit, even at the risk of his fortune and his life, anyone to do the least harm to these good people who had taken refuge with him. However, the following morning, the rumours had spread, and the dregs of the people assembled in front of his house and demanded he handed over the poor nuns under pain of seeing his house attacked and destroyed. The brave tanner found the means to get these poor religious out under good guard, and then, opening his doors to the bandits, he convinced them that there were none of these persons so disgracefully persecuted within his house.”

But, in the midst of all these critical events, what had happened to Sister Marie-Cherubine?

When the news came that the revolutionaries were on the point of attacking the convent of the nuns, those who were not of Austrian origin were, upon the advice of Father Passerat, sent back to their homes. A faithful friend, Father Trogher, gave them every help they needed for their journey, and in all haste he conducted six of them out of the capital. This was on 7th April in the morning.

The travellers made their way to Aix-la-Chapelle and there they found refuge with the Sisters of Saint Elizabeth. They were made welcome there with the most affectionate and hospitable charity. They assigned them a part of their own convent, where the refugees could carry out their regular exercises.

As for Sister Marie-Cherubine, she was not of their number. To escape the rioters, she had hurriedly put on the clothes of a woman of the lowest condition, and wore an old and threadbare shawl, which gave her the appearance of a vagabond. While she was finding her way out, she came to a church, which she entered for a few moments. There, in order not to attract attention, she sat down in a corner behind a pillar, but she was noticed nonetheless by the sacristan, who began to suspect that she was in fact an expert thief. He kept on his guard and kept watch over her in consequence.

The poor Sister thus had the happy chance of leaving Vienna. She then made her way to Keulen, where she arrived on Friday, 10th April. There, she was welcomed charitably by Baron de Lago, the brother-in-law of her former Mistress of Novices, Sister Maria Victoria, who had also taken refuge with him. The two religious thus had the consolation of spending a few days together with the charitable Baron, and enjoying his benevolent hospitality.

As soon as Sister Marie-Cherubine learnt that six of her fellow Sisters were at Aix-la-Chapelle, she hastened to rejoin them. She arrived there on 15th April. But soon, on 19th of the same month, she had to leave them to go to Tirlemont in Belgium and spend some days there in the bosom of her family. It is impossible to express the joy that they all experienced in seeing her again after so long a separation, and after many days of severe trials.

However, the fervent religious longed for the blessed moment when she would be able to recommence her life in the cloister. This was why, on 20th April, the very next day, she took leave of her good parents and friends, and went on to her fellow Sisters in Bruges, who were awaiting her arrival.

But what had become of the Sisters in Aix-la-Chapelle? We can once again admire the ways of the divine Providence. For six months these good religious remained with the Sisters of Saint Elisabeth. The Mother Superior of Vienna came to join them and Sister Maria Victoria, and fixed their residence in the same house, while waiting for better times. The Redemptorist Fathers occupied a convent at Wittem in Dutch Limburg, which was about 12 kilometres from Aix-la-Chapelle, and this was part of a hamlet near the town of Galoppe. They busied themselves in procuring a residence nearby for the Redemptoristine Sisters, to the effect that the 13th October saw the first Redemptoristine Convent established at Galoppe in Holland, between Maestricht and Aix-la-Chapelle.

Other Sisters came there from Austria, where religious affairs were not improving. This is why, in view of the cramped conditions in this house in Galoppe, it was judged urgent to build a new and bigger convent, and this took place at Partij, a little hamlet not far from the Fathers in Wittem. This Monastery was situated on the road between Wybre and Malines, and called Marienthal (Valley of Mary), and it was occupied by the Redemptoristines on 26th June 1851. – The convent of the Vienna Sisters was not restored to them until 1853.

So this is how the storm of persecution, in the hands of God, became the means of extending the Institute of the spiritual daughters of Saint Alphonsus even more widely. And this is how their enemies, who believed they had exterminated them forever, were the co-operators in their establishment in Holland.

To obtain an idea of the situation in the capital, it will be interesting to hear the accounts given by the newspapers and eye witnesses.

“In Vienna, the revolutionary mob set to work at the beginning of March. One morning, on 13th of this month, the rioters invaded the convent of the Redemptorist Fathers and ransacked it. The priests were forced to leave their house, put off their religious habit and put on lay clothes, and hide in the houses of some of their devoted friends. The Redemptoristines equally had to take shelter in some nearby houses.

“The weakness of the government had let everything take its course, and submitted without saying a word to the first demands of the revolutionaries. Calm was re-established for a moment in the city. It was concluded that the peril had been averted, so the Fathers and Sisters believed, in spite of the wise advice of their friends, that it was now possible to remain in their convents. This was on 30th March.

“But now on 6th April, in the morning, a troop of armed men made up of students and national guards invaded the Redemptorist convent, and roused up the furious crowd to believe that the priests did not deserve to remain any longer in Vienna. Some carriages were brought along and the Fathers were forced to get into them, and without being able to bring any of their things with them, they were driven outside the city. Rev. Father Passerat, their worthy Superior, an old man of 76, was so upset by this ignoble treatment that he lost his strength and fell when getting out of the carriage. These barbarians left him in the middle of the open country without paying the least attention to him.

“When the assault on the Redemptorist house had come to an end, the rioters now cried: ‘It’s the turn of the Sisters in Rennweg Street.’ And so their house was attacked on the evening of the same day, 6th April. At that moment, a large number of pious persons were in the chapel to attend benediction. The savage crowd which that morning had invaded the Fathers’ convent now invaded the nuns’ chapel. The chaplain was already at the altar, but these scoundrels would not permit him to begin the ceremony.

“The good Sisters were terrified and fled into their garden. The rabble had scarcely entered the convent when they gave free rein to their sacrilegious rage. Their impiety even went so far as to wrench a crucifix from the wall and trample it underfoot. They had carriages brought up and conducted the Sisters out of the city.

“A young revolutionary came up to one of these carriages, and noticing four religious in it, he spat at them as a sign of his profound contempt.

“Once outside the city, the Sisters were made to get out and they were left to go where they would. And so, as night fell, there were now thirty poor women, most of them very aged, who had been chased out of their house and forced to seek shelter in the darkness with whoever took compassion on them.

“Some of the Sisters, however, when the revolutionaries arrived, had found refuge with a neighbour, Mr. Goham, a tanner by profession, whose house adjoined the Monastery garden. This generous man declared that he would never permit, even at the risk of his fortune and his life, anyone to do the least harm to these good people who had taken refuge with him. However, the following morning, the rumours had spread, and the dregs of the people assembled in front of his house and demanded he handed over the poor nuns under pain of seeing his house attacked and destroyed. The brave tanner found the means to get these poor religious out under good guard, and then, opening his doors to the bandits, he convinced them that there were none of these persons so disgracefully persecuted within his house.”

But, in the midst of all these critical events, what had happened to Sister Marie-Cherubine?

When the news came that the revolutionaries were on the point of attacking the convent of the nuns, those who were not of Austrian origin were, upon the advice of Father Passerat, sent back to their homes. A faithful friend, Father Trogher, gave them every help they needed for their journey, and in all haste he conducted six of them out of the capital. This was on 7th April in the morning.

The travellers made their way to Aix-la-Chapelle and there they found refuge with the Sisters of Saint Elizabeth. They were made welcome there with the most affectionate and hospitable charity. They assigned them a part of their own convent, where the refugees could carry out their regular exercises.

As for Sister Marie-Cherubine, she was not of their number. To escape the rioters, she had hurriedly put on the clothes of a woman of the lowest condition, and wore an old and threadbare shawl, which gave her the appearance of a vagabond. While she was finding her way out, she came to a church, which she entered for a few moments. There, in order not to attract attention, she sat down in a corner behind a pillar, but she was noticed nonetheless by the sacristan, who began to suspect that she was in fact an expert thief. He kept on his guard and kept watch over her in consequence.

The poor Sister thus had the happy chance of leaving Vienna. She then made her way to Keulen, where she arrived on Friday, 10th April. There, she was welcomed charitably by Baron de Lago, the brother-in-law of her former Mistress of Novices, Sister Maria Victoria, who had also taken refuge with him. The two religious thus had the consolation of spending a few days together with the charitable Baron, and enjoying his benevolent hospitality.

As soon as Sister Marie-Cherubine learnt that six of her fellow Sisters were at Aix-la-Chapelle, she hastened to rejoin them. She arrived there on 15th April. But soon, on 19th of the same month, she had to leave them to go to Tirlemont in Belgium and spend some days there in the bosom of her family. It is impossible to express the joy that they all experienced in seeing her again after so long a separation, and after many days of severe trials.

However, the fervent religious longed for the blessed moment when she would be able to recommence her life in the cloister. This was why, on 20th April, the very next day, she took leave of her good parents and friends, and went on to her fellow Sisters in Bruges, who were awaiting her arrival.

But what had become of the Sisters in Aix-la-Chapelle? We can once again admire the ways of the divine Providence. For six months these good religious remained with the Sisters of Saint Elisabeth. The Mother Superior of Vienna came to join them and Sister Maria Victoria, and fixed their residence in the same house, while waiting for better times. The Redemptorist Fathers occupied a convent at Wittem in Dutch Limburg, which was about 12 kilometres from Aix-la-Chapelle, and this was part of a hamlet near the town of Galoppe. They busied themselves in procuring a residence nearby for the Redemptoristine Sisters, to the effect that the 13th October saw the first Redemptoristine Convent established at Galoppe in Holland, between Maestricht and Aix-la-Chapelle.

Other Sisters came there from Austria, where religious affairs were not improving. This is why, in view of the cramped conditions in this house in Galoppe, it was judged urgent to build a new and bigger convent, and this took place at Partij, a little hamlet not far from the Fathers in Wittem. This Monastery was situated on the road between Wybre and Malines, and called Marienthal (Valley of Mary), and it was occupied by the Redemptoristines on 26th June 1851. – The convent of the Vienna Sisters was not restored to them until 1853.

So this is how the storm of persecution, in the hands of God, became the means of extending the Institute of the spiritual daughters of Saint Alphonsus even more widely. And this is how their enemies, who believed they had exterminated them forever, were the co-operators in their establishment in Holland.

This necrology is translated from Fleurs de l'Institut des Rédemptoristines by Mr John R. Bradbury. The copyright of this translation is the property of the Redemptoristine Nuns of Maitland, Australia. The integral version of the translated book will be posted here as the necrologies appear.