Born Baroness d’Axter

I. Her life in the world. – The lady of honour.

On 24th January 1822 there was born in Ratisbon (Regensburg) the Servant of God whose life we will briefly recount. At baptism she received the names of Bertha-Genevieve-Josephine-Jeanne. Her father, Baron Louis d’Axter, was chamberlain to the King of Bavaria. Her mother, Josephine-Adelaide, Baroness de Verger, occupied herself especially with her family and the care of her subordinates. Their union was blessed, and God granted them a great number of children, and they applied themselves with all their powers to give them a truly Christian education.

From her earliest childhood, Bertha was distinguished by a lively spirit, a jovial character, and an unusually pleasant nature, and so she became the darling of her parents and the whole family. Her piety especially and her love of prayer attracted the attention of those who were witness to it. So one of her sisters wrote the following lines to her at the end of her life: “I still remember very often when we were young, how I saw you absorbed in prayer for entire hours, as pious as an angel, and I greatly regret now that I did not imitate your example better.”

The child was scarcely nine years old when death came to snatch her tender mother away from her. The whole time the illness of she who was everything to her lasted, Bertha admitted nothing that could soften or diminish her pain. Everything that her mother suffered she herself endured in the depths of her heart, and to preserve a life so precious to her, she would willingly have sacrificed her own. But the good God disposed otherwise. “The tree has fallen,” said Sister Marie-Rosalie’s historian, [1] “but the flower will never perish. Protected by the Sun of justice and covered by the beneficent shadow of the mystical Rose, she shall produce fruits in abundance, as Jesus Christ has chosen her for His spouse, and Mary for her beloved daughter.”

Bertha was sent to Munich, to pursue her education at the royal boarding-school for young ladies of the nobility. Everything was put in hand to respond to the views of Baron d’Axter, and to form her in such a manner that one day she would bring honour to the family and render service to society. Her father was not deceived in his expectations. As his daughter was endowed with more than ordinary talents, she made such progress in the different sciences to which the pupils were introduced, that her mistresses were able, a few years later, to confide the instruction of fifty children to her. Besides German, she knew French and Italian, had a deep understanding of music and drawing, and these different abilities were to be very useful to her later on. Add to this the natural qualities and advantages relieved by a noble frankness and modest gravity, and it will be understood why others were attracted to her and sought her conversation. And so, for ten years she fulfilled the duties of mistress at the boarding-school and all her pupils were indebted to her for solid instruction and a true piety.

This is how things were when in 1850, there arrived at Munich the Princess of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, born the Princess of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg. In the course of a visit to the boarding-school for noble ladies, she was struck by the rare qualities of the young mistress, and suggested she might like to enter the Court in the quality of a lady of honour. Bertha accepted. “In the measure,” says the historian, “that these two souls opened themselves to knowing each other mutually, there could be seen growing in them a reciprocal esteem and affection. Both of them had given themselves generously to the practice of the Christian virtues and encouraged each other mutually in works of charity.”

When the good Princess became a widow for the second time, she entered the Order of the Visitandines. But Providence opened a new way up to Bertha and introduced her as a governess in the house of Prince Charles-Antoine of Hohenzollern and his spouse Josephine, Grand Duchess of Baden. This Princess had, of her own accord, abjured Protestantism in order to enter the bosom of the Church. Among her six children, which she had reared with the greatest of care, there were two daughters, Stephanie and Mary, the first of whom was born in 1837 and the second in 1845. She believed she was not able to find a better governess for these two children than Baroness d’Axter, for whom she had conceived the highest esteem. So she begged her to be good enough to take upon herself their education. Bertha accepted with gratitude and went straight away to Dusseldorf, where the Prince and the Princess of Hohenzollern had their residence.

In this new position, the talent and virtue of the pious governess soon shone in the brightest light. In the midst of the brilliant life of high society, and in spite of her daily contacts with Protestants, she was able not only to preserve her faith intact, but even give an example of a true and sincere piety. Princess Josephine treated Bertha as a member of the family, and the young Stephanie, with whom she was especially occupied, showed her the most tender affection.

During their stay at Dusseldorf, Princess Stephanie and her governess would both leave in the early morning to go to the church of St. Andrew and assist in the sacrifice of the Mass. Refusing every place of honour, they would go and kneel down in a little chapel dedicated to St. Louis de Gonzaga and pray there with fervour. In the walks they took in town or in the countryside, they would ordinarily visit the sanctuaries that they encountered. Often they would also direct their steps towards establishments of education, or asylums for aged and sick women, or they even went to console the poor and infirm in their cottages. The needy greatly loved receiving these sorts of visits, because they were sure to receive a rich gift of money accompanied by words of consolation.

However, the idea of renouncing the world and embracing religious life occupied the spirit of the pious governess. As the time approached when the education of Princess Stephanie would come to an end, Bertha called with all her heart on the action of Providence. It happened when the young Princess married don Pedro V, the King of Portugal. This was in 1858. We shall not describe here the complex journey by which the governess’ vocation took her to the Order of the Redemptoristines. We shall instead show the affection which the new Queen of Portugal showed her, and so we shall quote the letter written by her to the new religious. The reader will find there a noble witness of gratitude rendered to the virtues of the servant of God.

Cintra, 1st August 1858.

“My dear and good Bertha,

“I shall continue to call you by this name so dear to my heart until the day when you make your oblation to God in the Institute which you have embraced, and in which you find the means to tend towards the end where we all hope to arrive if we walk unceasingly in the paths that God has traced out for us.

“These paths, although different, however, have this in common that very often they are steep, and that they all lead to the same end. This thought must console us and inspire us in the moments when sadness or despondency wish to take hold of us. It will serve to help us to bear our cross and find it less heavy, and find it even sweet and light.

“Since our separation, dear Bertha, our eyes have seen things of every kind. One thing is common to both of us, and it is that we have seen our desires come about, but not however without having experienced a moment of bitterness at the memory of what we have had to abandon. I avow frankly that I have already had homesickness many time, and have experienced an extreme desire to see my parents, my friends, and my place of birth. What weighs upon me especially, is the thought that I am bound forever to another family and another country, but it must indeed be so, and I render thanks to God for having arranged things in this fashion. For the rest, I must indeed offer up to the Lord these little disagreeable things in the midst of the happiness He has allowed me to enjoy, as my dear Pedro is truly my delight. He is so full of goodness towards me, and I have already spoken to him more than once of my good and dear Bertha.

“I have not been slow in experiencing that it is not so easy nor so agreeable a task to bear a crown in a country where there is so much to do, and where it is so difficult to act according to one's conscience and convictions, and where it is necessary to proceed with great caution so as not to harm the good cause, and often wait for a long time, and dissimulate when one is contradicted.

“Sometimes one loses courage. Ah, my good Bertha, we encounter as many miseries here as everywhere else! God alone can remedy them and I beg you not to forget the Church of Portugal in your prayers. Recommend it equally to the prayers of your pious Superior and the prayers of your holy community. How many times do I enthusiastically recall the beautiful and magnificent solemnities celebrated in the churches of Germany! Here I do not find the sober character and profound sentiments of the German people. Happily, my dear Pedro, who has a noble and generous heart, compensates me amply in return.

“My new family is good and charming.

“My dear Bertha, I think so often of you. I also think of our visits to the churches, our walks and our conversations of yesteryear. They are wonderful memories for me. Since that time I have had more than one experience. I have already learnt to understand life a little in its grave and serious side, and I can see that the greatest happiness of the years of our youth and virtue, is not to know many things that are the torment of this life. It is with the greatest happiness that I recall the happy years that we lived together in my father’s house – years, alas, that have passed so quickly!

“I have spoken enough about what concerns me, so let us speak now of you, dear Bertha. I have learnt (not from Dusseldorf, as it seems that there is no news of you there), I have learnt that you seem sad and despondent, and this troubles me. [2]

“Write to me as soon as you can, my dear Bertha, I beg you, and write to me in detail. You can count on my discretion. Do not forget that you are dealing with a heart that loves you and knows how to understand you. Also, you can be well persuaded that many persons cherish you and are devoted to you. I hope that my request will not seem indiscreet to you, as I do it in the name of the friendship that I bear you.

“Farewell, my dear Bertha. Please recommend me to the Reverend Mother Superior.

I embrace you cordially."

Stephanie.

II. Her entry into religion. – The virtues of the cloister.

We have said nothing about how the vocation of Baroness d’Axter was confirmed, nor by what mysterious ways God led her to the right end A powerful attraction to the cloister had been inspiring the pious governess for a long time with the desire to leave the world. She opened herself to her director, who dissuaded her from entering a contemplative Order. When a fortuitous circumstance having obliged her to address herself to another confessor, he happened to speak of the Redemptoristine Nuns. This name attracted the Baroness’ attention, who gathered all the information necessary, and then sought admission into the Convent of Marienthal. But how many obstacles rose up before her! The education of Princess Stephanie had not yet been completely achieved; that of Princess Marie seemed in its turn to require the care of her governess and the attachments to high society of the court, the extraordinary esteem given to our heroine – did not all this serve to delay her?

The engagement of Princess Stephanie to don Pedro, the King of Portugal, seemed to resolve the situation; but because of cholera, the marriage had to be postponed for six months. And what heart-ache this caused the Baroness! It required all the skill of the Princess Mother, all the influence she who was one day to be the Empress Augusta, to persuade her to spend a further six months in the world. Meanwhile, she made the acquaintance of her future fellow Sisters, and the Superiors could only applaud her courage and her constancy. Finally, on 10th May 1858, she entered the Convent of Marienthal, never to leave it again.

A remarkable thing! On the very same day, the priest who earlier had told the new postulant about the Order of the Redemptoristines, himself now entered the novitiate of the Redemptorist Fathers of Hamicolt, near Munster. This was on the feast of Our Lady of Mercy.

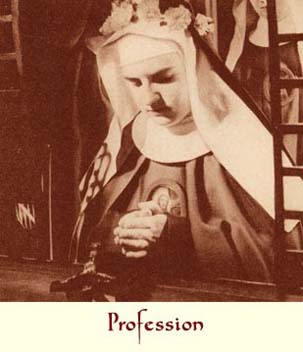

On the following 25th November, the chapel of the Sisters of Marienthal put on its festive finery. On the altar, around the tabernacle, was woven a crown of roses, and these roses had previously served as an ornament to Bertha’s clothes. As the Princess Mother of Hohenzollern could not attend the ceremony, she sent her son Antoine to take her place. She wrote to the Superior the day before: “It is with sincere regrets that I see myself obliged to excuse myself from coming to Convent of Marienthal for the Miss d’Axter’s ceremony of taking the habit. I would have been very happy to be able to be a witness to her happiness. My prayers will be united with your own on this solemn day, and I keenly regret not being able to tell her myself how much I rejoice in seeing her arrive at the fulfilment of her desires, enjoying the happiness and peace to which her soul aspires.”

The ceremony was a very touching one. Because of the great resemblance of her character and vocation to that of Saint Rosalie, they replaced the name of Bertha with that of this great Saint, and the new novice from then on was called Sister Marie-Rosalie of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary.

Her year in the novitiate was marked by several trials. Our good Sister’s zeal for penance brought her a severe illness from which she nearly died. She also had the sorrow of learning of the unexpected death of Princess Stephanie, Queen of Portugal, whom she loved so much. But she was consoled when she learned the circumstances of her death. On 16th July, when the Holy Viaticum was brought to the dying Queen, she replied with a lively faith and a great calm to the priest’s prayers. All the people surrounding her dissolved in tears. After remaining absorbed in prayer for a long time, she said to her man of confidence (?): “Oh well, if I must die, tell my parents that I love them, that I am thinking of my brothers and my sister, and all those who are dear to me, and I am resigned to the will of God.” As she said these words, she lifted her eyes up to heaven. Then she continued: “And also tell my parents that the King has made me truly happy, and that I recommend him to them. And now, my dear friend, receive my thanks again for the services you have rendered me.” At ten o’clock in the evening, Extreme Unction was ministered to her, and she followed all the prayers with attention. The Empress of Brazil placed a crucifix in her hands, and from time to time, when her breathing became more laboured, the Queen would put this crucifix to her lips, kiss it and say: “Jesus, Mary!” After eleven hours she went into agony, but she still had enough consciousness to reply to her confessor and the Empress. The King had already said his farewell to her, and overcome with grief, he was obliged to leave her. At one o’clock in the morning, on 17th July 1859, the Queen breathed her last.

Sister Marie-Rosalie had still other trials to bear. Spiritual aridities came to take away her heavenly consolations, and to make matters worse, she keenly felt the repugnance of her nature for a humble, mortified and penitent life. Add to this the fact that her ardour for mortification had to be moderated, which was a new source of abnegation. But her courage and her faith made her overcome all the difficulties, so much so that the famous Father Bernard, preaching the retreat in the Convent of Marienthal in 1859, gave this remarkable testimony to the novice’s virtue: “In general, I do not have much confidence in those persons who after living in high society, suddenly enter a rather severe Order, as ordinarily they do not persevere. But it is quite otherwise with Sister Marie-Rosalie. She has all the qualities you could wish for becoming a perfect Redemptoristine, and if she continues in this way, you need not be afraid of electing her as Superior, and she will bring honour to the convent.”

The premature death of our pious Sister did not allow us to see Father Bernard’s views come to pass, but it is of value at least to justify them with some details concerning the virtues of this servant of God.

First of all, humility seems to have rightly attracted her attention.

“For the pure love of God,” she wrote, “I am careful to make sure that no attention dictated by self-love or the desire to please finds its way into my actions.

“I am careful not to say a single word that expresses vainglory.

“I shall listen to others. I shall not defend my own way of seeing things. I shall be silent when I have a desire to speak.

“I shall do all I can to pass myself as ignorant and incapable, in place of flattering my self-love.

“In my relationship with others, I shall endure every disagreeable word with humility and joy, and I shall accept it in a spirit of penance as some small reparation for too great a confidence and for the eulogies and flattery that I have been the object of during my whole life.”

This was the programme that Sister Marie-Rosalie carried out. Let us listen to her historian. “Because of her excellent character and her pleasant manner, everyone loved her company, and nobody was embarrassed by her. Through her desire to advance in perfection, she humbly accepted all the corrections and remonstrances that were offered her either by her Superiors, or her inferiors, religious who were still young. She knew how to hide her talents and make them serve solely for the glory of God and the advantage of her neighbour. She never once spoke of the high rank that some members of her family occupied in society, and when, from time to time, she received a visit from some illustrious personage to the convent, she thought that it was not even worth the trouble of telling the community of these marks of distinction. She would have preferred to live unknown and forgotten. She greatly respected the converse Sisters and sometimes said: “I would give a lot to be in their place, provided that I could keep my breviary, as it would cost me a great deal if I had to make a sacrifice of it.”

This sincere humility was accompanied by a great spirit of mortification. She experienced an attraction for penance that one had no right to expect in a person who had lived in high society, in the midst of the eases and conveniences of life. So they very often had to forbid her to do mortifications which were clearly too much for her powers. But her spirit of sacrifice found a way to immolate even her tastes on this point. She was the author of these good resolutions:

“Spirit of sacrifice: For my sins and those of the world, I shall continue the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. The convent is like a funeral vault. Each cell is a tomb in which the religious offers herself to her heavenly Spouse like a living victim, and this offering is her joy and happiness. Each tear that drops at the foot of the cross, and every sigh that comes from her heart are counted. Every victory that we win over our passions and inclinations, all the daily pains that are found in religious life, and which we offer up to Our Lord, are so many new and magnificent pearls that will adorn our crowns in our heavenly abode.”

Such were her sentiments and her acts.

During her last illness, she received various candies and select delicacies from both the royal Hohenzollern family and some of the benefactors of the convent that were intended to fortify her. But she hardly touched them or not at all and preferred the community diet. She sometimes said in jest: “My stomach has become too rustic. I can no longer accept fine food.”

III. The virtues of the cloister. – Death in the cloister.

In consecrating herself entirely to God, Sister Marie-Rosalie intended to imitate Jesus Christ, her divine Redeemer, by the resolute offering of herself and the practice of the religious virtues. She also wished to draw from the Heart of her Saviour the graces necessary for this great enterprise, and she wrote these touching words at the head of her resolutions: “Resolutions taken at the feet of my crucified Saviour, in whose Heart I place them so that it may pour down upon me the grace and the courage necessary to observe them.” We have already quoted some of these resolutions, and now we quote the last one, so worthy of her devotion to the Blessed Virgin: “Mary is, after Jesus, my All and my Hope.”

Unreserved meditation on the truths of the faith was the basis of her interior life, and among these truths, the life of Our Lord was for her the object of a special and constant study. She did not limit herself to meditation, but she also loved to discuss, especially during her recreations, this subject so dear to her heart, and speak to her divine Master. She would say, quite rightly, that she often derived as much fruit from such discussions as from meditation itself. If she was tormented by interior pains, she would go into the chapel to open up her heart before the Blessed Sacrament, or else she would take the crucifix into her cell and speak to Jesus Christ her Saviour as if He was visibly present.

Meditation on the goodness of God towards her was familiar to her. Amongst the other benefits, she regarded her religious vocation as an evident proof of the divine mercy shown to her, and once she had been consecrated to Jesus Christ by the holy vows of religion, she hoped fervently that her divine Spouse would finish the work He had begun in her. A remarkable thing! She never had any temptation against her perseverance. One day (it was during her last illness) someone told her that a Father had remarked in a spiritual conference that in general no one was exempt from temptations against their vocation. “In that case”, she replied, “these temptations should hasten to come to me, otherwise, I shall die without having experienced them.”

She had a special talent for encouraging her Sisters, when she saw one of them sad or despondent. When anyone spoke with her about the account that we must render for God’s gifts and graces, she manifested her unwavering confidence and said, with a profound sentiment of conviction: “I cannot be persuaded that the good God would be so severe.” She spoke endlessly to her divine Spouse with the tone of the greatest familiarity. The beauties of nature revealed Him again to her heart. “O heaven, beautiful heaven!” she would often cry out when contemplating the magnificence of creation.

This marvellous confidence was founded upon a holy hatred of herself and an ardent love for God. She often recited this beautiful prayer:

“Myself, a poor and miserable nothing, I declare in the presence of my God that I wish to submit and sacrifice myself so as to do in everything His holy will, and seek nothing else, in all my actions, than His glory and His love. I vow and devote to Him all my being and all the moments of my life. Forever I shall belong to my beloved Jesus. I am His servant, His slave and His creature. Because He is everything to me, I am His unworthy bride, Sister Marie-Rosalie, dead to the world. Everything in God and nothing in me! Everything for God and nothing for me! A single heart, a single love, a single God!”

Inspired by such sentiments of love towards her Saviour, the pious Sister necessarily made rapid progress in perfection. There were many witnesses to the violence she did to herself to be rid of her imperfections, and to exercise herself continually in the so-called little virtues, which would certainly have cost her much effort.

For a person who had lived in high society, the virtue of poverty must have been more difficult for her to practise than the others. However, Sister Marie-Rosalie had so much love for it that she always sought out in preference what was the most poor. At table (and the Sisters noticed this) she would choose the morsels left over from the preceding meal, and the least appetising. In her last illness, when she was convinced that there was no longer any hope of a cure, she said: “Don’t let the doctor come again. This good man is in a dilemma because of me, because he can no longer cure me, and I too am also in a dilemma because of him.” But this was no more than a pretext not to cause expense to the house. In her last letter to the Princess of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, she said amongst other things that she considered herself happy to be able to sleep and die upon straw. In fact she had been insistently begging the Superior not to oblige her to make use of a mattress.

Her obedience to her Superiors was perfect, and she found this virtue easier to practise in the convent that at Court. She observed the Rules of the Institute with the greatest exactitude, especially in what concerned the common exercises. In her illnesses, she suffered more from not being able to keep up with the community than from her bodily pains.

As for the duty of fraternal charity, the Servant of God fulfilled it with a very special fervour. Her happy character, said Father Van Krugten, lent itself admirably to the common and social life. Considerate, helpful, and full of friendliness, she seemed but to live for others, and considered herself happy when she could do them good. She was one of those souls who knew how to subjugate hearts with an irresistible power and sacrifice herself for others. She loved all her fellow Sisters with the fullness of her heart, and in return she was loved by all. When she had some task to fulfil among the converse Sisters, she experienced a true pleasure in seeing them happy and content and she had for them all the charity of a mother for her children. When she was still in the world, she found herself frequently in contact with Protestants. She even had contacts with personages of so-called reformed religion, but these were relationships of pure civility and which did not cause any peril to her faith. The error and blindness in which these unfortunates found themselves afflicted her profoundly, so she did not cease to offer God her prayers and penance for their conversion.

A heroic patience crowned all these virtues. During the year 1860, following a cold snap, Sister Marie-Rosalie developed a violent cough that did not leave her. She was diagnosed with bronchitis. During the summer of 1862, the cough redoubled in intensity, especially at night. In October she also developed an internal inflammation which became incurable because the invalid’s body was unceasingly agitated by the violence of her cough. This complication caused her great pain, and the Servant of God understood that she did not have long to live. She asked the doctor if she was in danger of death, and when he in his turn, asked her if she desired to go to heaven, she replied: “Oh yes, and also to Purgatory, if this is the will of God.” When the doctor warned her that the end of her life was not far away, she expressed her gratitude for his care and trouble to him in such moving terms that the good doctor was astonished and extremely edified. Then she told her parents and the royal family of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen about her illness.

Her last farewells to her Sisters were imbued with the most lively faith. She told them how happy she was to die in religion, and warmly thanked each one of them for all the good that she had received from them. The thought of death did not terrify her at all. She discussed it with the Sisters in the calmest tone, and spoke of her funeral as if she was talking about someone else. During her long hours of suffering, her soul was lifted up to heaven and drew power and courage from it. One day, an infirmarian wished to close the window so that the invalid would not be inconvenienced by too much rough weather. Sister Marie-Rosalie told her quietly: “Oh, let me go on seeing beautiful heaven!”

On 9th January 1863, Extreme Unction was administered to her. She received it with great fervour. In the midst of her sorrows, she looked at the image of Jesus crucified and the Mother of Sorrows, and drew a sweet consolation from them. She also had a great devotion to Saint Joseph, and wanted to die on 19th March, the day of his feast. The Saviour, however, disposed otherwise. On the third Sunday after Easter, 26th April, the feast of the Patronage of Saint Joseph, at the request of the invalid, a little altar was put in her cell in honour of this great Saint. Her pains soon increased in a frightening manner. On Wednesday morning, they asked her if she wished to receive communion, and she made an affirmative sign in reply. After a few minutes of waiting, she then received holy communion and made a sign that she had been able to consume the sacred Host. Her hands crossed over her breast seemed to press her beloved Saviour against her heart one last time. Soon she entered into agony, and while the confessor and the Sisters were reciting the prayers of the agonising, Sister Marie-Rosalie peacefully rendered her soul up to God. This was on Thursday, 30th April 1863, on the feast of Saint Catherine of Siena.

Thus died this faithful servant of God, after having exchanged the splendours of the world for the obscurity of the cloister. Her religious life had been a short one, but marked by heroic virtues. Everyone’s hearts were united in praising her holy works and in proclaiming as blessed she who, in the example of Saint Agnes, had seen, loved and cherished with all her heart Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, the Saviour of mankind..

Footnotes

[1] Rev. Father Van Krugten, Redemptorist.

[2] Following her change of regime, and especially because of the summer heat, Sister Marie-Rosalie was indisposed for some time. Also, her Superiors took it upon themselves to moderate her desires for mortification and her aversion to exceptions. It was for this reason that Princess-mother Josephine urged her by letter to look after her health. Queen Stephanie was informed of it, and from this comes the allusion to her momentary despondency.

This necrology is translated from Fleurs de l'Institut des Rédemptoristines by Mr John R. Bradbury. The copyright of this translation is the property of the Redemptoristine Nuns of Maitland, Australia. The integral version of the translated book will be posted here as the necrologies appear.