Born Julienne Wold

Sister Marie-Raphael was born at Stein, in Upper Austria, on 6th January 1791. Her family were pious Christians, favoured by the gifts of fortune. One of her sisters entered the Carmelite Order. At first, Julienne, the youngest, did not feel the least inclined towards religious life, and her rare beauty inspired in her a vanity no less rare. But God, who wanted her for Himself alone, sent her various trials when she was quite young – first of all dropsy, then smallpox, which left her with numerous marks afterwards. And finally, she remained undersized and even a little deformed.

All this provided her with material for great sacrifices; but, although she was pious and good, she was still not yet convinced of the vanity of the world. The example of her sister brought her to confess herself to a Redemptorist Father, and this was the means which God used to attract her closer to Himself. Not that she greatly esteemed the sons of Saint Alphonsus. On the contrary, she had a sort of aversion for them, caused by the calumny that the hatred of the wicked had poured out against Saint Clement Marie Hofbauer and his disciples. So she never wished to be confessed by this great Servant of God, but after his death, she repented and set herself to following the direction given to her by the Redemptorists very faithfully. And when they told her about the Institute of the Redemptoristines, she felt herself drawn to ask for admission.

* * * * *

Different circumstances prevented her, however, including the question of knowing if this Order would ever obtain the Imperial authorisation, for which influential persons had made approaches for a long time, but with no success. The young lady was bold enough to ask for an audience with the Emperor Francis. Admitted into his presence, she asked him for the authorisation she desired so much, explaining to him point by point the reasons that Father Petrack, her confessor, and the Venerable Father Passerat had suggested to her. The Emperor replied to her with great goodness and assured her that he would take the matter in hand. She curtseyed, and she had hardly left the apartment when she remembered with alarm that she had forgotten a point. Without hesitating, she returned to the audience chamber and explained to the Emperor, who was still there, the point she had forgotten. The point was that her parents would not give her permission to enter the Order unless the Imperial authorisation was obtained. We can say immediately, that when the Emperor had signed the Decree authorising the Redemptoristine Institute in Austria at Pressburg on 11th November 1830, he had it sent, not to the Community of the Sisters, but to young Julienne who was still in the world, and it was she who gave it to the Sisters.

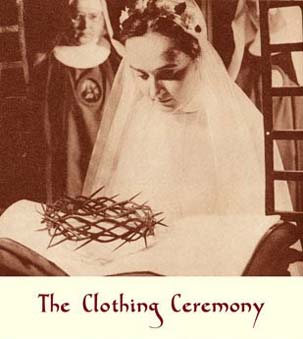

While waiting for the Emperor to keep his promise, Julienne learnt everything she thought would be useful in her future state of life. She even learnt the Latin language so that she would be able to understand the Divine Office. Finally, after an interruption of eighteen months, during which she had to care for her father in his last illness, she entered the Convent and received the habit and the name of Marie-Joseph-Raphael of the Five Wounds. The name of Joseph was given to her in addition because of her great devotion to this good Saint. In the month of January 1835, she made her profession and applied herself with redoubled fervour to all the exercises of religious life.

What distinguished her especially, with her love of regular observance, was her profound and sincere humility. She always considered herself the least worthy of God’s graces and judged herself useless at everything, so consequently she always chose the most humble tasks for herself. Inspired by a great spirit of penance, she practised severe mortifications, in spite of her delicate health, and her frequent migraines did not prevent her from always refusing any exception. Hard on herself, she was sweet and charitable towards her Sisters. Her concern for them was so great that she would even lose sleep over them, especially in her position as Mistress of Educandes, which she held for a long time. Always very conscientious in the use of her time, she never forgot, in spite of her great activity, to be closely united to God by continual prayer.

* * * * *

She was in the position of Mother Vicar when the Revolution of 1848 broke out. Forced to take refuge with her brother, she would soon have succumbed to privations and especially to the grief of being separated from her Sisters, if God had not opened the way to asylum for her at Marienthal in Holland. Back in her own element, she re-established herself and was once again, for the space of twelve years, the model of the Community, especially for her charity full of condescension, her humility and her love of her own abjectness. In spite of her indispositions, she continued to take part in community acts, even recreation, which she held quite correctly as a very important act of religious life. In her last years she suffered greatly in her legs. For three years, because of them she lost sleep almost completely.

So drained of her strength little by little, Sister Marie-Raphael ardently desired to be united forever with her heavenly Spouse. Whenever she learnt of the deaths of priests or Sisters younger than herself, she would envy their fate and wonder why God still left her in this world, she who was useless at everything. But God does not always judge like men. The hour of her deliverance finally arrived. On 25th January 1861, Sister Marie-Raphael received the holy Viaticum. “Come, O my Jesus, delay no longer!” she cried aloud. She often repeated this prayer until her death. On 27th, at about 9 pm in the evening, she rendered up her beautiful soul, while pronouncing the name of Jesus.

She was in her seventieth year.

All this provided her with material for great sacrifices; but, although she was pious and good, she was still not yet convinced of the vanity of the world. The example of her sister brought her to confess herself to a Redemptorist Father, and this was the means which God used to attract her closer to Himself. Not that she greatly esteemed the sons of Saint Alphonsus. On the contrary, she had a sort of aversion for them, caused by the calumny that the hatred of the wicked had poured out against Saint Clement Marie Hofbauer and his disciples. So she never wished to be confessed by this great Servant of God, but after his death, she repented and set herself to following the direction given to her by the Redemptorists very faithfully. And when they told her about the Institute of the Redemptoristines, she felt herself drawn to ask for admission.

* * * * *

Different circumstances prevented her, however, including the question of knowing if this Order would ever obtain the Imperial authorisation, for which influential persons had made approaches for a long time, but with no success. The young lady was bold enough to ask for an audience with the Emperor Francis. Admitted into his presence, she asked him for the authorisation she desired so much, explaining to him point by point the reasons that Father Petrack, her confessor, and the Venerable Father Passerat had suggested to her. The Emperor replied to her with great goodness and assured her that he would take the matter in hand. She curtseyed, and she had hardly left the apartment when she remembered with alarm that she had forgotten a point. Without hesitating, she returned to the audience chamber and explained to the Emperor, who was still there, the point she had forgotten. The point was that her parents would not give her permission to enter the Order unless the Imperial authorisation was obtained. We can say immediately, that when the Emperor had signed the Decree authorising the Redemptoristine Institute in Austria at Pressburg on 11th November 1830, he had it sent, not to the Community of the Sisters, but to young Julienne who was still in the world, and it was she who gave it to the Sisters.

While waiting for the Emperor to keep his promise, Julienne learnt everything she thought would be useful in her future state of life. She even learnt the Latin language so that she would be able to understand the Divine Office. Finally, after an interruption of eighteen months, during which she had to care for her father in his last illness, she entered the Convent and received the habit and the name of Marie-Joseph-Raphael of the Five Wounds. The name of Joseph was given to her in addition because of her great devotion to this good Saint. In the month of January 1835, she made her profession and applied herself with redoubled fervour to all the exercises of religious life.

What distinguished her especially, with her love of regular observance, was her profound and sincere humility. She always considered herself the least worthy of God’s graces and judged herself useless at everything, so consequently she always chose the most humble tasks for herself. Inspired by a great spirit of penance, she practised severe mortifications, in spite of her delicate health, and her frequent migraines did not prevent her from always refusing any exception. Hard on herself, she was sweet and charitable towards her Sisters. Her concern for them was so great that she would even lose sleep over them, especially in her position as Mistress of Educandes, which she held for a long time. Always very conscientious in the use of her time, she never forgot, in spite of her great activity, to be closely united to God by continual prayer.

* * * * *

She was in the position of Mother Vicar when the Revolution of 1848 broke out. Forced to take refuge with her brother, she would soon have succumbed to privations and especially to the grief of being separated from her Sisters, if God had not opened the way to asylum for her at Marienthal in Holland. Back in her own element, she re-established herself and was once again, for the space of twelve years, the model of the Community, especially for her charity full of condescension, her humility and her love of her own abjectness. In spite of her indispositions, she continued to take part in community acts, even recreation, which she held quite correctly as a very important act of religious life. In her last years she suffered greatly in her legs. For three years, because of them she lost sleep almost completely.

So drained of her strength little by little, Sister Marie-Raphael ardently desired to be united forever with her heavenly Spouse. Whenever she learnt of the deaths of priests or Sisters younger than herself, she would envy their fate and wonder why God still left her in this world, she who was useless at everything. But God does not always judge like men. The hour of her deliverance finally arrived. On 25th January 1861, Sister Marie-Raphael received the holy Viaticum. “Come, O my Jesus, delay no longer!” she cried aloud. She often repeated this prayer until her death. On 27th, at about 9 pm in the evening, she rendered up her beautiful soul, while pronouncing the name of Jesus.

She was in her seventieth year.

This necrology is translated from Fleurs de l'Institut des Rédemptoristines by Mr John R. Bradbury. The copyright of this translation is the property of the Redemptoristine Nuns of Maitland, Australia. The integral version of the translated book will be posted here as the necrologies appear.