The Monastery of Gagny.

Martha Hello (this was the family name of Sister Marie-Aloyse) was born in Paris on 5th February 1863. She was the fourth child who issued from the marriage of Mr. Charles Hello and Miss Gauthier of Saint-Michel, the worthy guardian of such a home. Her parents, who were profoundly convinced Christians, gave her an excellent education in the paternal home, so she practised good virtues from an early age. The family home, the castle of Keroman, in Brittany, saw her attain the most perfect obedience, and show charity towards the poor, and patience in illnesses. And what is worth even more, from her earliest years, she had the most tender devotion to the Blessed Virgin, whose colours she wore until the age of seven. Later on she was to write: “Ah, how much the holy Virgin protected me! Until I was seven, I was vowed to this good Mother, and then when I had to leave the blue and white, I remember that at Saint Merry, in Paris, there was a consecration of my little being to the Blessed Virgin, at her altar. How many prayers surrounded me, I cannot doubt! I attribute all of this as to why I was not in hell.” [1]

Martha made her first communion at the age of eleven, two weeks after having been received as a Child of Mary. Her joy on this wonderful day was immense. She seemed not to touch the ground, and her feet scarcely rested on the carpet with which the apartment had been furnished to honour the divine Host of her heart.

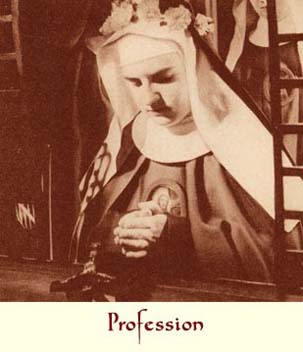

But trials were not long in coming. In 1879, Martha saw her brother Henri leave the paternal home to join his uncle, Father Hello, in the Congregation of Saint Vincent de Paul. Three years later, the head of the family, Mr. Charles Hello, a councillor at the Court of Appeal in Paris and a magistrate of great merit, was carried away from the affection of his family by a chest complaint. Six months after the illness of her father, the young lady revealed the secret of her heart, and, on the occasion of an offer of marriage, manifested her intention, or rather her firm decision, to leave the world. She then had some conflicts to go through, but her constancy triumphed over everything. After many prayers and much advice, she entered the Convent of the Redemptoristines of Grenoble on 15th February 1884. Less than a year afterwards, on 26th January 1885, she took the habit, and the following year, on the feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin, she made her profession. This was when, following the expression of one of her companions, Martha became Mary. And indeed she received as her name in religion the name of Sister Marie-Aloyse of the Divine Love.

* * * * *

In the admirable sermon that Father Hello gave on the day of his niece’s religious profession, he told her: “Sister Aloyse of the Love of God, launch yourself ardently into the career of the love of God which is open to you, and of which your name in religion will now remind you unceasingly. May your heart overflow with love, may it be wounded with the wounds of love that Our Lord bore on the Cross, and which have made the Saints all suffer and love so much. Do not be half-hearted in your desire for sanctity and in the giving of yourself to God.”

The newly-professed had been well prepared to follow these counsels, but she had to overcome herself, and she had a number of sacrifices to make. Let us now listen to one of her companions, who knew her very well.

“Sister Marie-Aloyse,” she said, “was an elect soul, great, generous, ardent, with an upright and powerful will that a certain native pride sometimes doubled with a little haughtiness, and even rigidity. As for her heart, it was excellent and sensitive, because it was always pure. However, for those who only judged her superficially, the cast of her mind, which was a little caustic, and where the occasion warranted it, had recourse to sarcasm, was capable of doing her great harm. It was not without some work that she was able to redress this little defective point in a good and noble character.

“The habitual cheerfulness of our good Sister, her spiritual and good-humoured conversations in the common recreations would have made anyone believe, at first sight, that joy was overflowing in her soul. This was not the case, however, at least for a certain number of years, and her constancy in covering an often very crucified interior state with a veil of the most gracious sweetness was no little proof of her virtue.

“Her zeal for souls was very ardent and effective. If the state of her health had permitted it, she would have imposed all sorts of penances upon herself for the sake of poor sinners and the souls in Purgatory. She supplied for this physical incapacity by a very sustained constancy in prayer and struggle against her defective tendencies ; every exterior shortcoming had its expiation in an exterior humiliation.

“As for her interior life, she loved to accuse herself in every detail to Our Lord Himself for her least oversights, and spiritual confession was one her favourite practices.

“The customary accusations regarding failures to observe the holy Rule or the Directory she did with great exactitude both in the refectory and in the Chapter of Faults, in terms well measured to put her to shame. She confessed to me a number of times that this cost her enormously. “I sweat on it,” she told me one day, when, for the twentieth time perhaps, she had added her formula of accusation, emphasizing the little word: again, which in the past had cost Rev. Father de Ravignan so much when he was a novice.

“Her exactitude in observing our holy Rule was in all respects absolutely exemplary. At the first sound of the bell, she would leave a letter unfinished, in order to fly to where the voice of God called her.

“Fly is indeed the word, and sometimes even, at the beginning of her religious life, she would fly a little too quickly, so quickly that they had to cut her wings a little. Reverend Mother then stopped her by a little admonition whose ordinary conclusion was to begin her journey again at a monastic pace.

“All our Sisters are also unanimous in testifying in favour of her perfect religious poverty. She kept nothing that was useless, and all the objects for her own use bore the stamp of her favourite virtue. She was very skillful in handing over to the officers what she thought was superfluous regarding clothes or work objects, and kept only what was strictly necessary. Even before she left the world, she exercised a great zeal in the practice of voluntary poverty.

“The virtue of the angels was of an immaculate whiteness in her. This dear little Sister was truly virginal and well merited to bear the name of the holy protector of pure souls, Saint Louis Gonzaga.

“She loved him greatly, her dear Patron. Each month she would prepare herself, by a very fervent novena, to celebrate the twenty-first day of the month in his honour, and how many times did she tell us that she had obtained from him, by this means, the most signal graces!

“As for the most excellent of all religious virtues, holy obedience, she took it so much to heart that she practised it a bit too much at the beginning, and we had to weigh our words when we gave her an obedience, as she was resolved to push the practice of it to the last limits of voluntary blindness.

“Her devotion in the tasks of refectory assistant, robe mistress, portress, sacristan and supervisor of the novitiate which were successively entrusted to her, left us nothing to desire, and her companions who had her for their assistant praise her exactitude, willingness, attention to rendering service, and her dependability.

“This last point cost her more than one struggle, and in return, it brought her many little victories, for as she had a lively mind and quick eyesight, it would take her a long time to come to a solution that she could accept there and then, and which she wanted to carry out in the same way.”

* * * * *

These most instructive details are completed by the following remarks which are no less interesting.

“One salient feature is missing from this sketch if we do not make a special mention of the little drop of spiritual originality which seasoned the words of Sister Marie-Aloyse and her whole manner of being. This often served to entertain us by inspiring the most amusing impromptu verse in her playful little mind. She was quite unique in this, and anyone else would have been hard put to try and imitate her.” This liveliness also comes across to us in the tone of sweet resignation which reigns in her letters. One day the good Sister was in the grip of painful suffering. She wrote to her brother who was a priest, Father Henri Hello:

“As you can see, your skinny sister is still on earth, in body and soul, and wishes to reassure you a little. I have been in my cell for a whole month now, but I’m getting better, however. Yet I still need a jolly good dose of your lovely prayers if I am to be patient and really cheerful, because I can see that I’m going to need you to make a sign of the cross over my health. The good God does all things well and He has chosen just the right moment to crucify me well and truly.

“Thank my good uncle for his letter, and be sure to tell him that I’m praying as much as I possibly can to be cured. But I’m beginning to run out of patience, because all the good saints are doing so well in Paradise that I think they’ve become a little bit deaf! However, Father Passerat has better hearing than Saint Anthony of Padua and Saint Francis Regis. To start with, I did a novena, which, they tell me, does many miracles. Oh yes for sure! Every day I got worse and on the ninth day I took to my bed. Then a Sister did a novena to Saint Regis for me, with the same result. These good saints can only hear together, I think. Finally Father Passerat gave me a little bit more strength.”

A tender and holy affection united Sister Marie-Alphonse to her brother Henri. The pious Redemptoristine was to make the sacrifice of her beloved brother twice in some way before her death. On two occasions, in fact, during his sister’s last months, Father Henri Hello was struck down by an illness which threatened to take him away from the affections of his family. On 19th July, the feast of Saint Vincent de Paul, he was struck down by a sudden illness which immediately put his life in danger. These are the terms in which the good nun expressed to her uncle the feelings that inspired these lines:

“What a dreadful surprise the letter I got from you yesterday has caused me! I would scarcely have expected such a cross, but nonetheless my heart remains full of hope.

“Your letter today is more reassuring, but this illness is so often mortal that, like you, I count even more on prayers, and the prayers of little children, than on remedies.

“The good Lord knows what this sacrifice has cost me, but He also knows that I am ready for whatever He wants, as His wisdom is infinite and everything He does is good.

“I was lying down in bed when your first letter reached me. I told the good Lord that it was sufficient for His very useless Sister to suffer, but her very useful brother ought to be cured. Not having permission to do more, I leave it to the good Lord to act.”

* * * * *

Many trials filled the career, outwardly so peaceful, of Sister Marie-Aloyse. Her almost constant condition of poor health was not the least of it, but this hard-working soul wanted to do nothing by halves, so she embraced the cross ardently. Let us listen to some more testimonies.

“What struck me the most about her, especially during the course of her last illness,” wrote the Sister Infirmarian, “was her indomitable energy in following, as far as lay in her power, all the spiritual exercises of the Community, aided by Reverend Mother and Mother Vicar. Her Infirmarian could give her no greater pleasure than to read out loud to her all the prayers of the Rule. She joined in them heart and soul, and she did so not just until her last day, but until the last moment of her life.”

Her Superior also says: “We would see her continuing to come to the refectory when she could no longer participate in the meals and even the very smell of the dishes would cause her nausea. This strength of will extended to everything. Sister Marie-Aloyse carried things so far, that sometimes, when she was full of sorrow, she would show herself happy and laughing during recreation, without letting anyone suspect how much pain she was in. We saw her, during her last illness, persisting in sleeping on one of the straw palliasses that the nuns use. The mere offer of a mattress caused her so much pain that we had to give up on making her accept it.

“Who knows the repugnance that sick people suffer? Sister Marie-Aloyse sometimes felt them profoundly, but her respect for poverty and her spirit of mortification made her over come all this. Whenever we mentioned a remedy or some kind of drink, she would hide her repugnance, and so that nothing would be lost, she would take everything we gave her without leaving anything. Those who have been ill for a long time find it nothing to laugh about.”

The death of Sister Marie-Aloyse was worthy of her life. At the age of thirty three (the age she wanted to die in order to imitate Our Lord), the valiant religious rendered her beautiful soul to God. This was on 17th October 1896, on the feast of the Blessed Marguerite Mary, the hard-working Visitandine who too had once bought, at the price innumerable victories over herself, the love of her beloved Saviour.

Martha made her first communion at the age of eleven, two weeks after having been received as a Child of Mary. Her joy on this wonderful day was immense. She seemed not to touch the ground, and her feet scarcely rested on the carpet with which the apartment had been furnished to honour the divine Host of her heart.

But trials were not long in coming. In 1879, Martha saw her brother Henri leave the paternal home to join his uncle, Father Hello, in the Congregation of Saint Vincent de Paul. Three years later, the head of the family, Mr. Charles Hello, a councillor at the Court of Appeal in Paris and a magistrate of great merit, was carried away from the affection of his family by a chest complaint. Six months after the illness of her father, the young lady revealed the secret of her heart, and, on the occasion of an offer of marriage, manifested her intention, or rather her firm decision, to leave the world. She then had some conflicts to go through, but her constancy triumphed over everything. After many prayers and much advice, she entered the Convent of the Redemptoristines of Grenoble on 15th February 1884. Less than a year afterwards, on 26th January 1885, she took the habit, and the following year, on the feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin, she made her profession. This was when, following the expression of one of her companions, Martha became Mary. And indeed she received as her name in religion the name of Sister Marie-Aloyse of the Divine Love.

* * * * *

In the admirable sermon that Father Hello gave on the day of his niece’s religious profession, he told her: “Sister Aloyse of the Love of God, launch yourself ardently into the career of the love of God which is open to you, and of which your name in religion will now remind you unceasingly. May your heart overflow with love, may it be wounded with the wounds of love that Our Lord bore on the Cross, and which have made the Saints all suffer and love so much. Do not be half-hearted in your desire for sanctity and in the giving of yourself to God.”

The newly-professed had been well prepared to follow these counsels, but she had to overcome herself, and she had a number of sacrifices to make. Let us now listen to one of her companions, who knew her very well.

“Sister Marie-Aloyse,” she said, “was an elect soul, great, generous, ardent, with an upright and powerful will that a certain native pride sometimes doubled with a little haughtiness, and even rigidity. As for her heart, it was excellent and sensitive, because it was always pure. However, for those who only judged her superficially, the cast of her mind, which was a little caustic, and where the occasion warranted it, had recourse to sarcasm, was capable of doing her great harm. It was not without some work that she was able to redress this little defective point in a good and noble character.

“The habitual cheerfulness of our good Sister, her spiritual and good-humoured conversations in the common recreations would have made anyone believe, at first sight, that joy was overflowing in her soul. This was not the case, however, at least for a certain number of years, and her constancy in covering an often very crucified interior state with a veil of the most gracious sweetness was no little proof of her virtue.

“Her zeal for souls was very ardent and effective. If the state of her health had permitted it, she would have imposed all sorts of penances upon herself for the sake of poor sinners and the souls in Purgatory. She supplied for this physical incapacity by a very sustained constancy in prayer and struggle against her defective tendencies ; every exterior shortcoming had its expiation in an exterior humiliation.

“As for her interior life, she loved to accuse herself in every detail to Our Lord Himself for her least oversights, and spiritual confession was one her favourite practices.

“The customary accusations regarding failures to observe the holy Rule or the Directory she did with great exactitude both in the refectory and in the Chapter of Faults, in terms well measured to put her to shame. She confessed to me a number of times that this cost her enormously. “I sweat on it,” she told me one day, when, for the twentieth time perhaps, she had added her formula of accusation, emphasizing the little word: again, which in the past had cost Rev. Father de Ravignan so much when he was a novice.

“Her exactitude in observing our holy Rule was in all respects absolutely exemplary. At the first sound of the bell, she would leave a letter unfinished, in order to fly to where the voice of God called her.

“Fly is indeed the word, and sometimes even, at the beginning of her religious life, she would fly a little too quickly, so quickly that they had to cut her wings a little. Reverend Mother then stopped her by a little admonition whose ordinary conclusion was to begin her journey again at a monastic pace.

“All our Sisters are also unanimous in testifying in favour of her perfect religious poverty. She kept nothing that was useless, and all the objects for her own use bore the stamp of her favourite virtue. She was very skillful in handing over to the officers what she thought was superfluous regarding clothes or work objects, and kept only what was strictly necessary. Even before she left the world, she exercised a great zeal in the practice of voluntary poverty.

“The virtue of the angels was of an immaculate whiteness in her. This dear little Sister was truly virginal and well merited to bear the name of the holy protector of pure souls, Saint Louis Gonzaga.

“She loved him greatly, her dear Patron. Each month she would prepare herself, by a very fervent novena, to celebrate the twenty-first day of the month in his honour, and how many times did she tell us that she had obtained from him, by this means, the most signal graces!

“As for the most excellent of all religious virtues, holy obedience, she took it so much to heart that she practised it a bit too much at the beginning, and we had to weigh our words when we gave her an obedience, as she was resolved to push the practice of it to the last limits of voluntary blindness.

“Her devotion in the tasks of refectory assistant, robe mistress, portress, sacristan and supervisor of the novitiate which were successively entrusted to her, left us nothing to desire, and her companions who had her for their assistant praise her exactitude, willingness, attention to rendering service, and her dependability.

“This last point cost her more than one struggle, and in return, it brought her many little victories, for as she had a lively mind and quick eyesight, it would take her a long time to come to a solution that she could accept there and then, and which she wanted to carry out in the same way.”

* * * * *

These most instructive details are completed by the following remarks which are no less interesting.

“One salient feature is missing from this sketch if we do not make a special mention of the little drop of spiritual originality which seasoned the words of Sister Marie-Aloyse and her whole manner of being. This often served to entertain us by inspiring the most amusing impromptu verse in her playful little mind. She was quite unique in this, and anyone else would have been hard put to try and imitate her.” This liveliness also comes across to us in the tone of sweet resignation which reigns in her letters. One day the good Sister was in the grip of painful suffering. She wrote to her brother who was a priest, Father Henri Hello:

“As you can see, your skinny sister is still on earth, in body and soul, and wishes to reassure you a little. I have been in my cell for a whole month now, but I’m getting better, however. Yet I still need a jolly good dose of your lovely prayers if I am to be patient and really cheerful, because I can see that I’m going to need you to make a sign of the cross over my health. The good God does all things well and He has chosen just the right moment to crucify me well and truly.

“Thank my good uncle for his letter, and be sure to tell him that I’m praying as much as I possibly can to be cured. But I’m beginning to run out of patience, because all the good saints are doing so well in Paradise that I think they’ve become a little bit deaf! However, Father Passerat has better hearing than Saint Anthony of Padua and Saint Francis Regis. To start with, I did a novena, which, they tell me, does many miracles. Oh yes for sure! Every day I got worse and on the ninth day I took to my bed. Then a Sister did a novena to Saint Regis for me, with the same result. These good saints can only hear together, I think. Finally Father Passerat gave me a little bit more strength.”

A tender and holy affection united Sister Marie-Alphonse to her brother Henri. The pious Redemptoristine was to make the sacrifice of her beloved brother twice in some way before her death. On two occasions, in fact, during his sister’s last months, Father Henri Hello was struck down by an illness which threatened to take him away from the affections of his family. On 19th July, the feast of Saint Vincent de Paul, he was struck down by a sudden illness which immediately put his life in danger. These are the terms in which the good nun expressed to her uncle the feelings that inspired these lines:

“What a dreadful surprise the letter I got from you yesterday has caused me! I would scarcely have expected such a cross, but nonetheless my heart remains full of hope.

“Your letter today is more reassuring, but this illness is so often mortal that, like you, I count even more on prayers, and the prayers of little children, than on remedies.

“The good Lord knows what this sacrifice has cost me, but He also knows that I am ready for whatever He wants, as His wisdom is infinite and everything He does is good.

“I was lying down in bed when your first letter reached me. I told the good Lord that it was sufficient for His very useless Sister to suffer, but her very useful brother ought to be cured. Not having permission to do more, I leave it to the good Lord to act.”

* * * * *

Many trials filled the career, outwardly so peaceful, of Sister Marie-Aloyse. Her almost constant condition of poor health was not the least of it, but this hard-working soul wanted to do nothing by halves, so she embraced the cross ardently. Let us listen to some more testimonies.

“What struck me the most about her, especially during the course of her last illness,” wrote the Sister Infirmarian, “was her indomitable energy in following, as far as lay in her power, all the spiritual exercises of the Community, aided by Reverend Mother and Mother Vicar. Her Infirmarian could give her no greater pleasure than to read out loud to her all the prayers of the Rule. She joined in them heart and soul, and she did so not just until her last day, but until the last moment of her life.”

Her Superior also says: “We would see her continuing to come to the refectory when she could no longer participate in the meals and even the very smell of the dishes would cause her nausea. This strength of will extended to everything. Sister Marie-Aloyse carried things so far, that sometimes, when she was full of sorrow, she would show herself happy and laughing during recreation, without letting anyone suspect how much pain she was in. We saw her, during her last illness, persisting in sleeping on one of the straw palliasses that the nuns use. The mere offer of a mattress caused her so much pain that we had to give up on making her accept it.

“Who knows the repugnance that sick people suffer? Sister Marie-Aloyse sometimes felt them profoundly, but her respect for poverty and her spirit of mortification made her over come all this. Whenever we mentioned a remedy or some kind of drink, she would hide her repugnance, and so that nothing would be lost, she would take everything we gave her without leaving anything. Those who have been ill for a long time find it nothing to laugh about.”

The death of Sister Marie-Aloyse was worthy of her life. At the age of thirty three (the age she wanted to die in order to imitate Our Lord), the valiant religious rendered her beautiful soul to God. This was on 17th October 1896, on the feast of the Blessed Marguerite Mary, the hard-working Visitandine who too had once bought, at the price innumerable victories over herself, the love of her beloved Saviour.

Footnotes

[1] Sœur Marie-Aloyse de l’amour de Dieu, rédemptoristine, Marthe Hello [Sister Marie-Aloyse of the Love of God, Redemptoristine], by Charles Maignen, a priest of the Fathers of Saint Vincent de Paul, Paris, imprimerie des Orphelins-Apprentis [press of the Orphan Apprentices], 40, rue de la Fontaine, 1897. A booklet of 50 pages.

This necrology is translated from Fleurs de l'Institut des Rédemptoristines by Mr John R. Bradbury. The copyright of this translation is the property of the Redemptoristine Nuns of Maitland, Australia. The integral version of the translated book will be posted here as the necrologies appear.