* * MONASTERY OF MARIENTHAL * *

History of the Foundation of the Monastery

History of the Foundation of the Monastery

The Revolution of 1848 drove Redemptorists and Redemptoristines from Vienna, these last were then governed by Mother Marie-Célestine.

All hope of recovering the Monastery having disappeared, they thought it a good idea to evacuate the foreign Sisters first of all from Vienna, and send them back home to their own country. These Sisters were seven in number, and some of them originally came from the Rhineland and the others from Holland. They had to go back to their countries of birth dressed in the clothes of the poor, bringing with them only the most necessary things. On 16th April 1848, they arrived at Aix-la-Chapelle. The following day, a relative of one of them came to meet her and bring her to the Redemptoristines of Bruges, where she had asked for admission. The six other Sisters refused point blank to be separated: they waited at Aix-la-Chapelle for the arrival of the Very Rev. Father Heilig, then the Provincial of the Belgian Province. They desired to place themselves under the direction of this excellent religious.

As soon as he arrived, the Very Rev. Father Heilig showed the refugees a lively compassion and took a truly paternal care of them. He also worked hard to find them a suitable habitation. Thanks to his intervention, the good Sisters of Saint Elizabeth in Aix-la-Chapelle offered them asylum in their convent. The offer was joyfully accepted and the poor exiles were thus able to find retreat in the cloister and the good things that it offered: the affection and tender charity of the Sisters of Saint Elizabeth added another prize.

The Very Rev. Father Provincial equally recommended the little community to the good care of the Very Rev. Father Koeman, Rector of the Redemptorists of Wittem. He also rendered his best services to the Sisters. Although they were confessed every week by the confessor of the convent that was sheltering them, they went every month to be confessed by the Rev. Father Rector at Wittem, and receive his direction. From time to time, Father Koeman would go to Aix-la-Chapelle, or rather, he would send a Father from his community there to give them a spiritual conference. The Venerable Father Passerat visited them twice, and this was a great consolation to them. On 8th June, Mother Marie-Célestine arrived, accompanied by Sister Marie-Victoria. The joy at seeing each other again was great, and the good Sisters of Saint Elizabeth, sharing in the common joy, gave the newly arrived their own cells. In the month of September Sister Marie-Madeleine finally arrived with two other converse Sisters: all of them were welcomed with great goodness and housed for fifteen days.

* * * * *

However, they had to think of leaving the Sisters of Saint Elizabeth, whose devotion and charity had been above every eulogy. After many enquiries, the Rev. Father Rector of the Redemptorists of Wittem found at Galoppe (Dutch Limburg), at half a league from Wittem, a suitable house. The Reverend Mother Superior took it on rent, and it was leased from the beginning of October.

The farewells to the good Sisters of Saint Elizabeth were very touching: no one could forget, or will ever forget how much they consoled the sorrows of exile. The Redemptoristines left their charitable house and entered that of Galoppe on 14th October. Rev. Father Koeman celebrated Mass there the next day and left the Blessed Sacrament and also blessed the house.

The joy of possessing a convent was great; the consolation of finding themselves under the direction of the Fathers of the Congregation was no less. The Sisters remained in this house until 26th June 1851. A short time afterwards, the Very Rev. Father Heilig, the Provincial, arrived. He told the community that he had consulted the superior authorities and the Rev. Father Rector of Wittem: they had decided to purchase the sisters a new convent, this time a definitive one. “No difficulty,” he added, “could arise here about the purchase of a new house, because in this country we enjoy a great religious liberty.”

However, there would be one condition for entry into this Monastery, and each Sister had to accept the following conditions in writing: “The convent of Vienna, if ever it can be re-established, the Sister undertakes to never return there, but to remain in this new foundation. She would also use in favour of this new Monastery whatever remains of her fortune.” This done, the Very Rev. Father Heilig came with Rev. Father Smetana, the Vicar General of the Congregation beyond the Alps, to examine all the details relative to the construction of the convent. The land was bought in a little place called Partij, near Wittem. The Monastery was to be built in conformity with all the prescriptions of the Rule; and also in conformity with religious poverty.

It was on 5th October 1849 that the first stone of the new convent was laid. The honour went to the Very Rev. Father Heilig, the Provincial; the Rev. Father Rector laid the second. At the beginning, the building offered great difficulties as the soil constantly subsided. It became impossible to lay bricks and they had to be supported by beams. The architect saw no danger at all; but the construction required a great deal of time and could only advance slowly.

If the joy of the Sisters had been great when they entered their rented house at Galoppe, it was even more so when they entered Marienthal (Valley of Mary) as this was the name that the Very Rev. Father Provincial gave the convent, to the great contentment of the Sisters. So as to avoid attracting the general attention, they made their entry in the most complete silence on 26th June 1851. The chapel was consecrated to Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows. It was blessed as was the entire convent, in the name of Mons the Bishop of Roermond, by Rev. Father Koeman. The day after this ceremony, the Rev. Father Rector celebrated the first Mass, and from then on the Redeemer established Himself in the new house to be its source of graces.

* * * * *

The convent of Marienthal was now finally established: the Revolution, in rudely shaking the tree of the Institute of the Redemptoristines, had succeeded only in scattering its seeds afar, and Satan’s plans had been foiled once again by divine Providence.

A short while afterwards, religion recovered a greater liberty in Austria, under the reign of the young and pious Emperor Franz Joseph. On 23rd June 1852, the Sovereign signed a decree permitting the Redemptorists and Redemptoristines to re-enter the country, and the convent in Vienna was re-opened. At the same time a new foundation was also opened at Ried, in Lower Austria. The Sisters who were destined for this Monastery left the solitary cloister of Marienthal, which was so dear to them. They did not in the least doubt that great trials would crown their sacrifice. On 24th November they received the news of the death of Sister Marie-Xaviera and the great danger of death facing the Mother Superior. Then there was an epidemic of smallpox that ravaged the country and attacked the nuns. The Superior, Mother Marie-Madeleine, only recovered after long sufferings, but she did recover; may Our Lord be praised for it! Without her, this foundation would have suffered a great loss, and the return to Vienna could not have been made. Sister Marie-Madeleine had to leave the convent of Ried in 1853 in order to re-establish the convent of Vienna, and she was accompanied by two Sisters from Marienthal. Sister Marie-Victoria was then appointed to lead the Monastery of Ried.

However, the convent of Marienthal prospered more and more, and before the Kulturkampf burst onto the scene, there were plans to found a house in the Rhineland provinces. A large property was bought in the area of Koblenz-Vallenduri; and the Sisters had already been designated for this foundation, when the tempest of persecution broke out in fury against all the Catholic institutions of the German Empire. Later on, the house was sold at a loss, as there was no longer any hope of re-establishing it. In its place, the convent of Sambeek was founded near Boxmeer, in the north of Dutch Brabant. All the Sisters who were sent there, number 10 in all, were Dutch, except for the Superior. This house prospered rapidly and was visibly blessed from on high.

* * * * * * * * * *

In 1877, the convent of Marienthal was, in its turn, visited by a trial: a fire broke out and it destroyed it from top to bottom. This was on 25th January, the day when the Order pays very special honour to the holy Child Jesus. The beautiful Christmas crib was still exposed, and the novices had just offered up their last prayers to the divine Saviour there. Suddenly a cloud of smoke rose up from the Crib. A novice saw it and let out a cry, but it was too late! A piece of paper had caught fire from one of the candles surrounding the artificial rocks, and the flames soared up. A wooden wall which touched the crib and went up to the attic now caught fire in its turn. Soon the whole building was captured by the flames, in spite of incredible efforts by the Redemptorist Students and the people from nearby who came running at the sound of the alarm. This was right in the middle of the night. The fire pumps failed and everyone had to resign themselves to seeing their beautiful Monastery burn down. All that was left were the exterior walls. However, many objects were snatched from the flames, thanks to the devotion of the Students and at least there was no loss of life. The roof of the chapel was entirely consumed, but they were able to save the Blessed Sacrament and the most precious objects.

The same evening, the Rev. Father Rector of Wittem, later Mons. Wulfingh [1] left for the Franciscan Sisters at Nonnenwerth. They had rented an old mansion at Maastricht so they would have somewhere to go if they were persecuted. They immediately deferred to the Rev. Father Rector’s wishes and offered their hospitality to the Sisters of Marienthal. It was in this house, called “the Great Swiss House” that the community lived until the month of October of the same year. At this time, part of the new convent of Marienthal was built and finished.

“The good Fathers of Wittem offered us the greatest charity in these sorrowful circumstances. During the first week of our emigration, the Students and a converse Brother worked actively to put our house in order. From the spiritual point of view, we were very privileged. Three Fathers came in turn to the “Great Swiss House” and preached conferences for us every week. We also had the great happiness of possessing the Blessed Sacrament in this place of exile.

“When the tragedy became known, we received so many marks of sympathy and different kinds of gifts that it would take too long here to mention the names of our benefactors and the nature of their gifts. But the consolation and joy which came to us from our Holy Father, Pope Pius IX, is something we cannot fail to mention. When the Holy Pontiff heard the news about the fire, he asked for more information through the Nuncio in Holland, Mons. Capri. After he received the information he wanted from the Rev. Father Rector of Wittem, the Nuncio sent the sum of 3000 francs for the Redemptoristines of Marienthal. This generous gift, offered by the Vicar of Jesus Christ on earth, filled every heart with joy. We immediately sent the Holy Father, and also the Nuncio, the expression of our profound gratitude.

“Thanks to the speed with which the work of reconstruction was conducted, after three months of exile we were able to leave the “Great Swiss House” and return to our own Monastery. On 10th October the last Sisters arrived. Every time a carriage stopped in front of the convent, the three bells filled the air with their joyous song. Each time too, our hearts beat in unison. Gradually, as everything was repaired, we reverted to the customs of the former Monastery. The following year, we lost the last Choir Sisters who had suffered expulsion from Vienna, Sister Marie-Anne-Joseph and Mother Marie-Celestine. They died ten days apart.”

Some years later, the convent of Marienthal, which was now more flourishing than ever, was to introduce the Redemptoristines into America, and for the first time the Daughters of Saint Alphonsus brought the New World the help of their prayers and sacrifices. [2]

All hope of recovering the Monastery having disappeared, they thought it a good idea to evacuate the foreign Sisters first of all from Vienna, and send them back home to their own country. These Sisters were seven in number, and some of them originally came from the Rhineland and the others from Holland. They had to go back to their countries of birth dressed in the clothes of the poor, bringing with them only the most necessary things. On 16th April 1848, they arrived at Aix-la-Chapelle. The following day, a relative of one of them came to meet her and bring her to the Redemptoristines of Bruges, where she had asked for admission. The six other Sisters refused point blank to be separated: they waited at Aix-la-Chapelle for the arrival of the Very Rev. Father Heilig, then the Provincial of the Belgian Province. They desired to place themselves under the direction of this excellent religious.

As soon as he arrived, the Very Rev. Father Heilig showed the refugees a lively compassion and took a truly paternal care of them. He also worked hard to find them a suitable habitation. Thanks to his intervention, the good Sisters of Saint Elizabeth in Aix-la-Chapelle offered them asylum in their convent. The offer was joyfully accepted and the poor exiles were thus able to find retreat in the cloister and the good things that it offered: the affection and tender charity of the Sisters of Saint Elizabeth added another prize.

The Very Rev. Father Provincial equally recommended the little community to the good care of the Very Rev. Father Koeman, Rector of the Redemptorists of Wittem. He also rendered his best services to the Sisters. Although they were confessed every week by the confessor of the convent that was sheltering them, they went every month to be confessed by the Rev. Father Rector at Wittem, and receive his direction. From time to time, Father Koeman would go to Aix-la-Chapelle, or rather, he would send a Father from his community there to give them a spiritual conference. The Venerable Father Passerat visited them twice, and this was a great consolation to them. On 8th June, Mother Marie-Célestine arrived, accompanied by Sister Marie-Victoria. The joy at seeing each other again was great, and the good Sisters of Saint Elizabeth, sharing in the common joy, gave the newly arrived their own cells. In the month of September Sister Marie-Madeleine finally arrived with two other converse Sisters: all of them were welcomed with great goodness and housed for fifteen days.

* * * * *

However, they had to think of leaving the Sisters of Saint Elizabeth, whose devotion and charity had been above every eulogy. After many enquiries, the Rev. Father Rector of the Redemptorists of Wittem found at Galoppe (Dutch Limburg), at half a league from Wittem, a suitable house. The Reverend Mother Superior took it on rent, and it was leased from the beginning of October.

The farewells to the good Sisters of Saint Elizabeth were very touching: no one could forget, or will ever forget how much they consoled the sorrows of exile. The Redemptoristines left their charitable house and entered that of Galoppe on 14th October. Rev. Father Koeman celebrated Mass there the next day and left the Blessed Sacrament and also blessed the house.

The joy of possessing a convent was great; the consolation of finding themselves under the direction of the Fathers of the Congregation was no less. The Sisters remained in this house until 26th June 1851. A short time afterwards, the Very Rev. Father Heilig, the Provincial, arrived. He told the community that he had consulted the superior authorities and the Rev. Father Rector of Wittem: they had decided to purchase the sisters a new convent, this time a definitive one. “No difficulty,” he added, “could arise here about the purchase of a new house, because in this country we enjoy a great religious liberty.”

However, there would be one condition for entry into this Monastery, and each Sister had to accept the following conditions in writing: “The convent of Vienna, if ever it can be re-established, the Sister undertakes to never return there, but to remain in this new foundation. She would also use in favour of this new Monastery whatever remains of her fortune.” This done, the Very Rev. Father Heilig came with Rev. Father Smetana, the Vicar General of the Congregation beyond the Alps, to examine all the details relative to the construction of the convent. The land was bought in a little place called Partij, near Wittem. The Monastery was to be built in conformity with all the prescriptions of the Rule; and also in conformity with religious poverty.

It was on 5th October 1849 that the first stone of the new convent was laid. The honour went to the Very Rev. Father Heilig, the Provincial; the Rev. Father Rector laid the second. At the beginning, the building offered great difficulties as the soil constantly subsided. It became impossible to lay bricks and they had to be supported by beams. The architect saw no danger at all; but the construction required a great deal of time and could only advance slowly.

If the joy of the Sisters had been great when they entered their rented house at Galoppe, it was even more so when they entered Marienthal (Valley of Mary) as this was the name that the Very Rev. Father Provincial gave the convent, to the great contentment of the Sisters. So as to avoid attracting the general attention, they made their entry in the most complete silence on 26th June 1851. The chapel was consecrated to Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows. It was blessed as was the entire convent, in the name of Mons the Bishop of Roermond, by Rev. Father Koeman. The day after this ceremony, the Rev. Father Rector celebrated the first Mass, and from then on the Redeemer established Himself in the new house to be its source of graces.

* * * * *

The convent of Marienthal was now finally established: the Revolution, in rudely shaking the tree of the Institute of the Redemptoristines, had succeeded only in scattering its seeds afar, and Satan’s plans had been foiled once again by divine Providence.

A short while afterwards, religion recovered a greater liberty in Austria, under the reign of the young and pious Emperor Franz Joseph. On 23rd June 1852, the Sovereign signed a decree permitting the Redemptorists and Redemptoristines to re-enter the country, and the convent in Vienna was re-opened. At the same time a new foundation was also opened at Ried, in Lower Austria. The Sisters who were destined for this Monastery left the solitary cloister of Marienthal, which was so dear to them. They did not in the least doubt that great trials would crown their sacrifice. On 24th November they received the news of the death of Sister Marie-Xaviera and the great danger of death facing the Mother Superior. Then there was an epidemic of smallpox that ravaged the country and attacked the nuns. The Superior, Mother Marie-Madeleine, only recovered after long sufferings, but she did recover; may Our Lord be praised for it! Without her, this foundation would have suffered a great loss, and the return to Vienna could not have been made. Sister Marie-Madeleine had to leave the convent of Ried in 1853 in order to re-establish the convent of Vienna, and she was accompanied by two Sisters from Marienthal. Sister Marie-Victoria was then appointed to lead the Monastery of Ried.

However, the convent of Marienthal prospered more and more, and before the Kulturkampf burst onto the scene, there were plans to found a house in the Rhineland provinces. A large property was bought in the area of Koblenz-Vallenduri; and the Sisters had already been designated for this foundation, when the tempest of persecution broke out in fury against all the Catholic institutions of the German Empire. Later on, the house was sold at a loss, as there was no longer any hope of re-establishing it. In its place, the convent of Sambeek was founded near Boxmeer, in the north of Dutch Brabant. All the Sisters who were sent there, number 10 in all, were Dutch, except for the Superior. This house prospered rapidly and was visibly blessed from on high.

* * * * * * * * * *

In 1877, the convent of Marienthal was, in its turn, visited by a trial: a fire broke out and it destroyed it from top to bottom. This was on 25th January, the day when the Order pays very special honour to the holy Child Jesus. The beautiful Christmas crib was still exposed, and the novices had just offered up their last prayers to the divine Saviour there. Suddenly a cloud of smoke rose up from the Crib. A novice saw it and let out a cry, but it was too late! A piece of paper had caught fire from one of the candles surrounding the artificial rocks, and the flames soared up. A wooden wall which touched the crib and went up to the attic now caught fire in its turn. Soon the whole building was captured by the flames, in spite of incredible efforts by the Redemptorist Students and the people from nearby who came running at the sound of the alarm. This was right in the middle of the night. The fire pumps failed and everyone had to resign themselves to seeing their beautiful Monastery burn down. All that was left were the exterior walls. However, many objects were snatched from the flames, thanks to the devotion of the Students and at least there was no loss of life. The roof of the chapel was entirely consumed, but they were able to save the Blessed Sacrament and the most precious objects.

The same evening, the Rev. Father Rector of Wittem, later Mons. Wulfingh [1] left for the Franciscan Sisters at Nonnenwerth. They had rented an old mansion at Maastricht so they would have somewhere to go if they were persecuted. They immediately deferred to the Rev. Father Rector’s wishes and offered their hospitality to the Sisters of Marienthal. It was in this house, called “the Great Swiss House” that the community lived until the month of October of the same year. At this time, part of the new convent of Marienthal was built and finished.

“The good Fathers of Wittem offered us the greatest charity in these sorrowful circumstances. During the first week of our emigration, the Students and a converse Brother worked actively to put our house in order. From the spiritual point of view, we were very privileged. Three Fathers came in turn to the “Great Swiss House” and preached conferences for us every week. We also had the great happiness of possessing the Blessed Sacrament in this place of exile.

“When the tragedy became known, we received so many marks of sympathy and different kinds of gifts that it would take too long here to mention the names of our benefactors and the nature of their gifts. But the consolation and joy which came to us from our Holy Father, Pope Pius IX, is something we cannot fail to mention. When the Holy Pontiff heard the news about the fire, he asked for more information through the Nuncio in Holland, Mons. Capri. After he received the information he wanted from the Rev. Father Rector of Wittem, the Nuncio sent the sum of 3000 francs for the Redemptoristines of Marienthal. This generous gift, offered by the Vicar of Jesus Christ on earth, filled every heart with joy. We immediately sent the Holy Father, and also the Nuncio, the expression of our profound gratitude.

“Thanks to the speed with which the work of reconstruction was conducted, after three months of exile we were able to leave the “Great Swiss House” and return to our own Monastery. On 10th October the last Sisters arrived. Every time a carriage stopped in front of the convent, the three bells filled the air with their joyous song. Each time too, our hearts beat in unison. Gradually, as everything was repaired, we reverted to the customs of the former Monastery. The following year, we lost the last Choir Sisters who had suffered expulsion from Vienna, Sister Marie-Anne-Joseph and Mother Marie-Celestine. They died ten days apart.”

Some years later, the convent of Marienthal, which was now more flourishing than ever, was to introduce the Redemptoristines into America, and for the first time the Daughters of Saint Alphonsus brought the New World the help of their prayers and sacrifices. [2]

Footnotes

[1] Mons. Wulfingh died at sea in 1906 while returning to Surinam.

[2] The story of this foundation in Canada will be told later on.

Mother Marie-Celestine of the Five Wounds, O.SS.R. Foundress of the Monastery of Marienthal at Wittem (1808 - 1878)

Born Cecile Stenitzer

Born Cecile Stenitzer

Cecile Stenitzer was the youngest of fourteen children that God granted her good parents. She was born in Upper Styria, in Austria, on 30th September 1808, at Gös, a short distance away from Leoben, where her parents retired to later. One of her brothers died at the age of twelve. While the pious child was in his agony, his mother sat beside his bed and wept. Suddenly the child told her, “Don’t weep, mother, but get up quickly. Can’t you see the beautiful Lady entering here?” As soon as he spoke these words he died, leaving behind the sweet hope that he had seen the Queen of the Angels appearing to him.

Cecile herself owed a great deal to Mary’s protection. One day she swallowed a piece of lead and found herself in the most perilous state. Her mother immediately promised to make a pilgrimage in honour of the Blessed Virgin, and she was fortunate enough to be able to take the piece of metal out of her daughter’s throat that was choking her. Another time Cecile was out on the street and was knocked down by a horse, but she did not receive the least injury.

She made her first communion at the age of nine, but without the necessary preparation. In fact, we can only say that Christian life was languishing in Leoben at this time. Those who should have been instructing the faithful and leading them to good were of a distressing tepidness, and although Cecile’s parents were not lacking in piety, they were too immersed in the affairs of the world to be able to supervise the education of their children very actively. Then the worries of the household, the crowd of visitors and the great number of domestic servants were for Cecile the cause of a great number of distractions and impressions harmful to her soul. She said later on, “I did not see too much good, but rather too much evil, and the worst was that I was led into not seeing it as such.” Add to this her outgoing and jovial nature, and her pleasant manners, and it can be seen how great the peril was to which she was exposed.

However, God had chosen her for Himself. She often experienced a strong attraction for solitude, and the desire to pray and weep over the frivolities of her youth. Even then she was filled with a tender devotion for the Five Wounds of Our Lord, and every evening, before taking her repose, she was in the habit of kissing a crucifix suspended above her bed. One evening, weariness made her forget about it, but she suddenly remembered it, and generously breaking with the sleep that was weighing upon her, she got up and devoutly venerated the Saviour’s wounds. This little sacrifice was the first moment when the divine love triumphed in her soul. God in His turn, covered her with His buckler against every seduction and kept her entirely for Himself.

* * * * *

At this time, religious life was very little known in Leoben and even less valued. So it is not astonishing that Cecile thought more about marriage than any other state of life. Moreover, her fortune, her beauty and her lovable character brought her many admirers. Amongst them, two managed to capture the attention of the young girl for quite a time. One day, however, when one of them, having invited her to walk unaccompanied with him, made her a dishonest proposition, she suddenly saw a very fine young man appear, whose presence confounded the tempter. Cecile believed with good reason that it was an apparition of her guardian angel. Another day, a young officer who had been courting her was permitted some liberty, and she cried out and showed him an image of the Blessed Virgin. “No, no! What would the Mother of God and the Child Jesus say?” And she ran away. The officer was sent elsewhere and Cecile was left alone. Later on she said: “I was like a fly hovering above the boiling water without falling in.” Praise be to the mercy of God, we can state here that Cecile kept the lily of her virginity and her baptismal innocence intact until the hour of her death. This is what resulted from her own confession.

However, she was not yet entirely God’s. But then the moment arrived. One evening when she could not get off to sleep, it came to her in spirit that, on the same bed where she was lying, her young niece, aged eight, had died a short time before. Then the thought of death, judgement and hell profoundly pierced her soul. It was as if someone had told her: “If you continue living like this, you will be damned.” The flames and pains of hell, she admitted later, were so vividly represented to me that I was quite overcome and filled with a dreadful fear. I found myself suddenly changed and I resolved to convert myself. In the light of the eternal flames, the truths of the faith appeared to me on that very extraordinary day, and as they had never been shown to me before.

From that moment her resolutions corresponded to the greatness of the grace received. Here are some of them: “Struggle courageously against the inclinations of your nature. – Fast every Friday on bread and water, and take nothing then before evening. – Sleep on a plank on Friday nights. – Every day, for the space of half an hour, deplore the sins you have committed. – Do not eat fruit, except on Sundays. – Pray every evening until midnight. – Never go to the theatre or the ball. – Get rid of all vain objects. – Take the discipline every day, if it is possible. – Attend Mass every day and receive the sacraments often.”

Whatever opinion one may have on these different resolutions, it was the last point that was the most difficult for Cecile, because of the lack of religious spirit that reigned in Leoben, where piety had turned into derision. She was often very distressed to find herself deprived of this support and lack any good spiritual direction. However God was to provide. From Mautern, a locality not far from Leoben, the Redemptorist Fathers would come from time to time into her town, and beginning in 1829, they would descend to the hotel belonging to Cecile’s parents. But she had been warned against them by the public opinion of the people of Leoben, who depicted the “Liguorians” as “fanatics” and would mock anyone who went to be confessed by them, and so at first she hesitated in making use of their ministry.”

Finally she overcame her fear, and although she was exposed to the laughter of the world, she presented herself in the missionaries’ confessional. The first ones she met were the disciples of the blessed Father Clement-Marie Hofbauer. Soon afterwards, it was the venerable Father Joseph Passerat, the Vicar General of the Redemptorists who heard her. She placed herself entirely under his direction and made a general confession to him, and from then on her ideas of religious life became a firm resolution to leave the world and consecrate herself irrevocably to God. It was then that she learned one day from one of her friends that there was a Redemptoristine convent in the capital of Austria. She conceived a vivid desire to enter it, but as soon as she spoke of it, opposition to it burst out from every side. Parents, friends and even the pious people in Leoben rose up against her; the whole town, we might say, conspired against her design. And several times she was forced to absent herself by fleeing from the temptations of seduction. Her mother, who was sixty-six years old, claimed she could not manage without her daughter, who alone was capable of managing the house. Her father refused to give her any part of her inheritance. But Cecile placed her trust in God and was fortified by the decision of Father Passerat who managed to obtain her admission. She separated herself from her weeping family without herself shedding a single tear. This was on 1st June 1829. She was then only 20 years old.

* * * * *

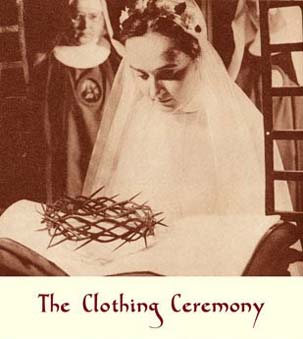

Scarcely had she entered the convent when God, to purify her, made her severely expiate the pleasures and faults of her past life. The Monastery of Vienna was only a temporary house, and the situation there was precarious, as the Emperor had not yet legally authorised the Institute. The Sisters called themselves Penitent Sisters. But there were many other painful subjects capable of discouraging a less courageous postulant. The Superior, Mother Marie-Alphonse, was French and knew the German language only very imperfectly, and consequently she could converse only slightly with the young postulant placed under her direction. Also, she found herself confined to a very small cell, and she was given the task of patching the vestments. After having been up till then, we might say, the principal object of the attention and esteem of her parents, she who had directed the affairs of her house, now saw herself as if neglected or given tasks which did not in the least seem suitable for her. But the courageous young lady realised that she had not entered the convent with any other aim than triumphing over herself, and she had an unequalled occasion there to carry out her first resolution, that of overcoming all her repugnances. An interior dryness, a terrible disgust, temptations against the faith, all worked to deliver the most horrible assaults upon her, but she held firm in spite of everything, supported by her obedience to her venerable director, who was also prey at this time to the most severe tribulations. Finally the Emperor authorised the Institute (November 1830), and on the following 8th February she received the red habit with ten other novices. And then Father Passerat gave her the significant name of Sister Marie-Celestine of the Five Wounds. Finally, on 2nd October 1832, after a novitiate that the laws of the Empire had prolonged by eight months, she made the entire sacrifice of herself by her religious profession.

It was soon evident how serious her oblation had been after such a long and severe preparation. Named Assistant to the Mistress of Educandes, she was distinguished by her fervour, and her profound and continual recollection, but also by a great goodness and a rare affability. Knowing the human heart very well, she was able to guess the interior struggles that the Sisters had to endure, and address them by means of words of encouragement and consolation. After having fulfilled various tasks, in 1839 she was elected Vicar, and at the canonical election of 1841, the choice of the Sisters made her the Superior. She was only thirty three years old.

Shaken by this unexpected choice, Mother Marie-Celestine was as if choked by her tears, and according to the expression of one of the Sisters present (later Mother Marie-Gabrielle of the Incarnation), she was like a lamb that was led to the slaughter. – Her government was stamped even more with the Spirit of God. The Venerable Father Passerat, who knew her so well and was so good a judge in matters of spirituality, gave this precious testimony of her: “Mother Marie-Celestine has acquitted herself in a perfect manner of all the tasks that have been confided to her.” Returning after her triennium to the exercise of obedience and recollection, she tried to obscure herself entirely and we may say that she was no longer found except in choir or in her cell. It was about this time that with Father Passerat’s consent, she made the vow of always doing what she recognized as being the most perfect.

In 1847, the confidence of the Sisters called her once more to the task of Superior. This time, the tribulations came from the outside. The Revolution of 1848 had broken out. When they saw the signs of it, the Redemptoristines of Vienna omitted nothing to divert the anger of God. Continual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, prayers to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, penances – nothing was left undone, but the chalice of tribulation had been prepared and it had to be drunk.

Mother Marie-Celestine did it with an intrepid heart. On 6th April 1848, the insurgents assailed the Redemptorist convent in the morning. In the evening, at five o’clock, they attacked that of the Sisters, who scarcely had the time to flee through a breach in the garden wall. More than the others, the Superior was the object of pursuit by the rebels. She had to separate herself from her daughters and, with a broken heart, wander from one house to another belonging to the relatives and friends of the Sisters. And what did she not suffer then, seeing her daughters dispersed, denuded of everything, with no hope of being reunited again! Finally she found refuge with Baron Lago, the relative of one of her Sisters, and she remained in hiding in their house for the space of six weeks. She did everything she could to at least keep the property of the convent and the church, but it was all in vain. She even had to leave Vienna again in all haste with the family that had sheltered her. Soon afterwards, the suppression of the Order was decreed, and there was nothing else the poor Mother could do than rejoin some of her daughters who had found refuge with the Sisters of Saint Elizabeth at Aix-la-Chapelle, and who ardently desired her to come to them.

However, our divine Redeemer wished to draw good out of evil. The tempest which seemed to have destroyed everything determined the foundation of a new monastery in a country which had not possessed one before, and the convent of Vienna was soon able to be re-established. From Aix-la-Chapelle, the Sisters directed their steps to Holland, the hospitable land where since 1835 the Redemptorist Fathers had possessed at Wittem a former Capuchin convent founded in 1732, the same year that Saint Alphonsus had instituted the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer. In the village of Galoppe, not far from Wittem, a provisional monastery was being prepared for the Sisters, and Mother Marie-Celestine and her daughters made their entry there on 14th October of this same year of 1848. The enclosure was established. The next day, on the feast of Saint Teresa, the Sisters once more put on the habit of the Order, and everyone, after the first Mass celebrated in this sacred asylum, renewed their religious vows. The joy and gratitude of the Mother and her daughters was great and reached its peak when, after three years of waiting, the community was able to make its entry into the new Monastery of Marienthal, built in the village of Wittem, not far from the convent of the Redemptorist Fathers.

* * * * *

And now Mother Marie-Celestine had been chosen by God as the foundress of this new Monastery which was to give birth to many others, in particular the first Redemptoristine foundation across the Ocean. And she was to govern this house which until our own days has remained a model of regular observance, sanctity and apostolic spirit.

She fulfilled her mission with a zeal worthy of a true spouse of Jesus Christ, worthy of a privileged soul and endowed from her earliest years with very special graces. The Ven. Father Passerat, who visited her sometimes in her new abode, and the Superiors of the Convent of Wittem judged it necessary for her to continue exercising the functions of Superior, although her triennium had expired. The necessary dispensations were easily obtained. Under her government, the Monastery soon began to prosper. Her activity successfully faced all the difficulties in the beginning and soon the vocations came forward. The Order of the Redemptoristines having been re-established in Austria (1853), Mother Marie-Celestine generously made the sacrifice of two of her daughters, Mothers Marie-Victoria and Marie-Aloysia, the one being elected as the Superior of Ried and the other of Vienna. But God compensated her amply, so much so that, six years after her entry into Marienthal, the buildings were found to be insufficient to cope with the number of vocations, and they had to be extended.

Re-elected Superior in 1857, the good Mother then had a thought most worthy of her great heart. As a true daughter of the Church, she wished to console the heart of Pius IX by giving him news of the Monastery and asking for his holy blessing. Her letter was accompanied by several pictures painted by the nuns. Here is the text:

Most Holy Father,

“Sister Marie-Celestine of the Five Wounds of Jesus Christ, Superior of the Religious of the Most Holy Redeemer in the Convent of Marienthal, Diocese of Roermond, in Holland, - most humbly prostrated at the feet of Your Holiness, takes, in the name of her community, the respectful liberty of expressing to the Holy See and to the most worthy successor of Saint Peter the sentiments of profound veneration and entire devotion by which the spiritual daughters of Saint Alphonsus de Liguori are animated in regard to the common Father of the faithful.

“We always remember with a sweet consolation, Most Holy Father, the great part that Your Holiness played in the destiny of the Daughters of Saint Alphonsus at the time of trials in 1848, when they were victims of the revolution in the capital of Austria. Chased from Vienna, they took refuge in a solitary place in the Dutch province of Limburg, where, first of all renting a little house, they lived together in community, observing as far as was possible the Rules of their holy Institute. After surmounting many obstacles, we had the happiness of constructing a regular monastery with a little chapel. But what gave us the greatest happiness was that Your Holiness deigned, by a quite extraordinary favour, to bless our enterprise and grant our new foundation canonical approval, dated from 30th January 1852.”

Since this time, the Lord has filled us with graces, as although we are living in a Protestant kingdom, we nonetheless enjoy a happy liberty which has given us every facility for observing our holy Rules to the letter. Moreover, the Lord has favoured us with numerous and good vocations. Many persons from the best families in society have asked for and obtained their admission into our new monastery, delivering themselves now heart and soul to the contemplative life, the principal aim of our Order. We are already twenty five religious, and our monastery is no longer sufficient for so many requests for admission, and we see ourselves obliged to think of increasing the present buildings of our convent considerably, with the consent of our Most Reverend Bishop.

“So now we come before you very humbly to ask for Your Holiness’ blessing upon our new enterprise and especially upon the community of Religious Redemptoristines of Marienthal. So give us a place in Your paternal heart, Most Holy Father, and keep us always under Your beneficent protection. Thus united in heart and spirit to the visible Head of our Mother the Holy Church, we shall be able entreat the Father of mercies with greater confidence to fill Your Holiness with the consolations and graces necessary for the government of the Church. And in truth, we are already obliged by our holy Rules to offer up our prayers daily for the needs of the Church; but the numerous proofs of paternal charity that Your Holiness has given us up till this moment, leads us and obliges us in a particular manner to say special prayers for the happiness and preservation of Your sacred person.

“And so, Most Holy Father, please accept the sentiments of gratitude, respect and devotion that Your spiritual daughters of Marienthal offer You. Humbly prostrated at the feet of Your Holiness, I dare once again to reiterate my respectful request for You to give me Your holy blessing, and to also especially bless each one of my spiritual daughters.

“With the most profound respect,

“Your Holiness’ most humble and obedient servant.

“Sister MARIE-CELESTINE of the five sacred wounds of Jesus Christ.”

Marienthal, 21st March 1858.

This letter was to go straight to the paternal heart of Pius IX. The holy Pontiff deigned to send the following reply on 14th July of the same year. We translate it from the Latin.

PIUS IX, Pope.

To our dear Daughter Marie-Celestine of the five sacred Wounds of Jesus Christ.

“Dear Daughter in Jesus Christ, greetings and apostolic blessing.

Your letter of 21st March last has reached us. It is a new and dazzling witness of your filial devotion towards us, your faith, your piety and your obedience. It has mitigated the sorrow that we experienced long ago when we learnt that in the very grave political troubles, turbulent and seditious men chased you away from your house in Vienna and sent you into exile. It has been a great consolation for us to learn from your letter that in the midst of these troubles and tempests you have been able to find a safe and tranquil asylum in Holland where you can attend in peace to the duties of your holy state, and where your religious Institute has recruited numerous vocations. Blessed be God, the Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ, whose Providence has thus determined many people to let themselves be guided by the example of your virtues and embrace religious life!

“You must thus recognize all the blessings of the divine clemency with the greatest zeal and walk with the greatest eagerness in the way of perfection. Apply yourselves with all your powers, my dear daughters in Jesus Christ, to practise these virtues which have cast the greatest lustre on this brilliant model of sanctity, Saint Alphonsus de Liguori, your Father. Never once cease to honour and serve, with an entirely filial zeal and piety, the most holy Mother of God conceived without original stain, through whom God willed all graces should come to us continually. Remember also every day in your prayers our own feebleness, so that our actions and efforts may contribute to the greatest glory of the name of God and the good of all the faithful.

“As a measure of Our paternal charity, for you and your companions, and as a harbinger of heavenly grace, We give you with Our love, to both you, dear Daughter in Jesus Christ and to all your Sisters, Our apostolic blessing.

“Given at Rome, the seat of Saint Peter, on 14th July 1858 in the thirteenth year of our Pontificate.

“PIUS IX, Pope.”

This letter from the Vicar of Jesus Christ was a great consolation for the faith and apostolic zeal of Mother Marie-Celestine and encouraged her singularly in the exercise of her charge. And indeed she was re-elected Superior in 1863 and 1871, in spite of her sickly state. This languor began in 1859, at the time of the first death that took place in the new monastery. A remarkable circumstance marked this first departure for heaven. In 1849, and at the beginning of the foundation, Mother Marie-Celestine had instantly asked the Lord not to let any Sister die before ten years had elapsed, and this was to let the community be established solidly. She was heard to the letter, but at the same time she received, until her death, the prerogative of bodily sufferings which often confined her to a bed of sorrows. The death of her long-time companions and the departure of two other Sisters for the Convent of Vienna which was then suffering, were all new crosses for her heart. These crosses, it is true, found some compensation in the joy of a new foundation established at Sambeek in Dutch Brabant in 1874. Thirteen Sisters were sent there. Mother Marie-Celestine succeeded in the same year in dissuading her daughters from their plan to re-elect her, and she even begged the Bishop of Roermond not to grant the dispensation required. She was named Mother Vicar, and while she was exercising this charge, she suffered the terrible trial of the year 1877, when the Convent of Marienthal became the prey of flames. The poor Mother, suffering and confined to bed, was brought by the Countess of Ansembourg to her mansion at Galoppe. When she felt a bit better, she joined her Sisters who had found refuge near Maastricht, and re-entered Marienthal with them in the month of October 1877.

From this time on her life was simply a long succession of sufferings. According to the doctor, her last long illness was accompanied by sorrows such that the doctor had never seen greater. To these exterior pains was added an interior abandonment which afflicted her to a supreme degree. Since she was thirty she had never tasted consolations, but this time, it was rather a moral agony to which no one could supply a remedy. And yet, in the depths of this resolute soul, the Lord imbued a powerful grace that sustained her without her realising it and helped her prepare herself for her eternal wedding. This sorrowful preparation, according to God’s plan, was to replace the religious help which ordinarily was not lacking in the monasteries. The death of Mother Marie-Celestine was most unusual. On 12th December 1878, the community was reciting the Office of the Dead for a Sister who had died at Sambeek. Suddenly some noises could be heard coming from the Infirmary. They ran there in all haste and found the dead body of Mother Marie-Celestine sitting in her chair, dressed in the habit of the Redemptoristines. She had reached the age of seventy, and she had spent nearly fifty of them in the Order of the Most Holy Redeemer.

A wise and strong woman, a great and generous soul, with a tender and solid devotion, endowed with a sure and practical common sense, full of faith and a very active love, she was, for nearly half a century, the pillar and strength of the Order of the Redemptoristines beyond the Alps. As a Superior, she united a very maternal goodness and tenderness with a wise rigour for the observance of the Rules, always avoiding the extremes. She had a special talent for consoling the afflicted and souls who were tempted. In her general conduct there was nothing arrogant, nothing hard or harsh. Cheerful and gentle in conversation, she made the best impression on strangers.”

The source of her great strength of soul and the immense services she rendered the Order was her profound humility, her love of obedience and the hidden life, and especially her love of prayer. The Venerable Father Passerat once called her a soul of prayer. And it was especially before the Blessed Sacrament that she opened up her soul, and found strength and light for herself and for the matters that she was responsible for. She truly merited the title of Bride of the Blessed Sacrament. Her soul is depicted marvellously in Farewell to the Blessed Sacrament that she loved to recite: “Farewell, my Jesus, farewell, my Spouse, remember Your bride in Your mercy. I recommend to the holy Wound in Your side, all my interests, those that are mine and those of this community and the entire Order. Through Your holy wounds and Your blood, be propitious and merciful to us, O my Jesus. Through Your blessing that I ask of You and without which I shall not leave You, ensure that I live uniquely for You in love and reverence. While I am waiting, I leave my heart before Your tabernacle like a burning lamp, with the most lively desire that every time it beats it will praise and glorify You in my place during my absence, in the sentiments that inspire Your adorable Heart in this sacrament of love.” Mother Marie-Celestine also had a very special devotion for the Mother of Sorrows, and she took her as Patron for the chapel in Marienthal. She propagated her cult in the new Monastery. She counselled her Sisters to have recourse continually to this tender Mother in all their needs and in all the difficulties and contradictions that they would have to suffer. “One Ave Maria on these occasions,” she would say, “is worth more that all your words and all your complaints. I have often had this experience.”

One day, a novice who was strongly tempted to abandon her vocation went to tell her of all her pain and ask her for permission to leave. The good Mother replied to her that it was the will of God for her to remain in the monastery. She encouraged her and made the sign of the cross on her forehead, saying: “Jesus crucified be in all my thoughts! Jesus crucified be in all my words! Jesus crucified be in my heart!” The temptation disappeared immediately and the novice persevered.

May these words, which are like the motto of a Redemptoristine, be confirmed in all the daughters of St. Alphonse who recognize a model and mediatrix in Mother Marie-Celestine. May this worthy Bride of Jesus Christ, through the effect of her words, live especially in the hearts of all the Redemptoristines of Marienthal, for was she not their Foundress, was she not their Mother, through her love, her actions and especially through her sufferings?

Cecile herself owed a great deal to Mary’s protection. One day she swallowed a piece of lead and found herself in the most perilous state. Her mother immediately promised to make a pilgrimage in honour of the Blessed Virgin, and she was fortunate enough to be able to take the piece of metal out of her daughter’s throat that was choking her. Another time Cecile was out on the street and was knocked down by a horse, but she did not receive the least injury.

She made her first communion at the age of nine, but without the necessary preparation. In fact, we can only say that Christian life was languishing in Leoben at this time. Those who should have been instructing the faithful and leading them to good were of a distressing tepidness, and although Cecile’s parents were not lacking in piety, they were too immersed in the affairs of the world to be able to supervise the education of their children very actively. Then the worries of the household, the crowd of visitors and the great number of domestic servants were for Cecile the cause of a great number of distractions and impressions harmful to her soul. She said later on, “I did not see too much good, but rather too much evil, and the worst was that I was led into not seeing it as such.” Add to this her outgoing and jovial nature, and her pleasant manners, and it can be seen how great the peril was to which she was exposed.

However, God had chosen her for Himself. She often experienced a strong attraction for solitude, and the desire to pray and weep over the frivolities of her youth. Even then she was filled with a tender devotion for the Five Wounds of Our Lord, and every evening, before taking her repose, she was in the habit of kissing a crucifix suspended above her bed. One evening, weariness made her forget about it, but she suddenly remembered it, and generously breaking with the sleep that was weighing upon her, she got up and devoutly venerated the Saviour’s wounds. This little sacrifice was the first moment when the divine love triumphed in her soul. God in His turn, covered her with His buckler against every seduction and kept her entirely for Himself.

* * * * *

At this time, religious life was very little known in Leoben and even less valued. So it is not astonishing that Cecile thought more about marriage than any other state of life. Moreover, her fortune, her beauty and her lovable character brought her many admirers. Amongst them, two managed to capture the attention of the young girl for quite a time. One day, however, when one of them, having invited her to walk unaccompanied with him, made her a dishonest proposition, she suddenly saw a very fine young man appear, whose presence confounded the tempter. Cecile believed with good reason that it was an apparition of her guardian angel. Another day, a young officer who had been courting her was permitted some liberty, and she cried out and showed him an image of the Blessed Virgin. “No, no! What would the Mother of God and the Child Jesus say?” And she ran away. The officer was sent elsewhere and Cecile was left alone. Later on she said: “I was like a fly hovering above the boiling water without falling in.” Praise be to the mercy of God, we can state here that Cecile kept the lily of her virginity and her baptismal innocence intact until the hour of her death. This is what resulted from her own confession.

However, she was not yet entirely God’s. But then the moment arrived. One evening when she could not get off to sleep, it came to her in spirit that, on the same bed where she was lying, her young niece, aged eight, had died a short time before. Then the thought of death, judgement and hell profoundly pierced her soul. It was as if someone had told her: “If you continue living like this, you will be damned.” The flames and pains of hell, she admitted later, were so vividly represented to me that I was quite overcome and filled with a dreadful fear. I found myself suddenly changed and I resolved to convert myself. In the light of the eternal flames, the truths of the faith appeared to me on that very extraordinary day, and as they had never been shown to me before.

From that moment her resolutions corresponded to the greatness of the grace received. Here are some of them: “Struggle courageously against the inclinations of your nature. – Fast every Friday on bread and water, and take nothing then before evening. – Sleep on a plank on Friday nights. – Every day, for the space of half an hour, deplore the sins you have committed. – Do not eat fruit, except on Sundays. – Pray every evening until midnight. – Never go to the theatre or the ball. – Get rid of all vain objects. – Take the discipline every day, if it is possible. – Attend Mass every day and receive the sacraments often.”

Whatever opinion one may have on these different resolutions, it was the last point that was the most difficult for Cecile, because of the lack of religious spirit that reigned in Leoben, where piety had turned into derision. She was often very distressed to find herself deprived of this support and lack any good spiritual direction. However God was to provide. From Mautern, a locality not far from Leoben, the Redemptorist Fathers would come from time to time into her town, and beginning in 1829, they would descend to the hotel belonging to Cecile’s parents. But she had been warned against them by the public opinion of the people of Leoben, who depicted the “Liguorians” as “fanatics” and would mock anyone who went to be confessed by them, and so at first she hesitated in making use of their ministry.”

Finally she overcame her fear, and although she was exposed to the laughter of the world, she presented herself in the missionaries’ confessional. The first ones she met were the disciples of the blessed Father Clement-Marie Hofbauer. Soon afterwards, it was the venerable Father Joseph Passerat, the Vicar General of the Redemptorists who heard her. She placed herself entirely under his direction and made a general confession to him, and from then on her ideas of religious life became a firm resolution to leave the world and consecrate herself irrevocably to God. It was then that she learned one day from one of her friends that there was a Redemptoristine convent in the capital of Austria. She conceived a vivid desire to enter it, but as soon as she spoke of it, opposition to it burst out from every side. Parents, friends and even the pious people in Leoben rose up against her; the whole town, we might say, conspired against her design. And several times she was forced to absent herself by fleeing from the temptations of seduction. Her mother, who was sixty-six years old, claimed she could not manage without her daughter, who alone was capable of managing the house. Her father refused to give her any part of her inheritance. But Cecile placed her trust in God and was fortified by the decision of Father Passerat who managed to obtain her admission. She separated herself from her weeping family without herself shedding a single tear. This was on 1st June 1829. She was then only 20 years old.

* * * * *

Scarcely had she entered the convent when God, to purify her, made her severely expiate the pleasures and faults of her past life. The Monastery of Vienna was only a temporary house, and the situation there was precarious, as the Emperor had not yet legally authorised the Institute. The Sisters called themselves Penitent Sisters. But there were many other painful subjects capable of discouraging a less courageous postulant. The Superior, Mother Marie-Alphonse, was French and knew the German language only very imperfectly, and consequently she could converse only slightly with the young postulant placed under her direction. Also, she found herself confined to a very small cell, and she was given the task of patching the vestments. After having been up till then, we might say, the principal object of the attention and esteem of her parents, she who had directed the affairs of her house, now saw herself as if neglected or given tasks which did not in the least seem suitable for her. But the courageous young lady realised that she had not entered the convent with any other aim than triumphing over herself, and she had an unequalled occasion there to carry out her first resolution, that of overcoming all her repugnances. An interior dryness, a terrible disgust, temptations against the faith, all worked to deliver the most horrible assaults upon her, but she held firm in spite of everything, supported by her obedience to her venerable director, who was also prey at this time to the most severe tribulations. Finally the Emperor authorised the Institute (November 1830), and on the following 8th February she received the red habit with ten other novices. And then Father Passerat gave her the significant name of Sister Marie-Celestine of the Five Wounds. Finally, on 2nd October 1832, after a novitiate that the laws of the Empire had prolonged by eight months, she made the entire sacrifice of herself by her religious profession.

It was soon evident how serious her oblation had been after such a long and severe preparation. Named Assistant to the Mistress of Educandes, she was distinguished by her fervour, and her profound and continual recollection, but also by a great goodness and a rare affability. Knowing the human heart very well, she was able to guess the interior struggles that the Sisters had to endure, and address them by means of words of encouragement and consolation. After having fulfilled various tasks, in 1839 she was elected Vicar, and at the canonical election of 1841, the choice of the Sisters made her the Superior. She was only thirty three years old.

Shaken by this unexpected choice, Mother Marie-Celestine was as if choked by her tears, and according to the expression of one of the Sisters present (later Mother Marie-Gabrielle of the Incarnation), she was like a lamb that was led to the slaughter. – Her government was stamped even more with the Spirit of God. The Venerable Father Passerat, who knew her so well and was so good a judge in matters of spirituality, gave this precious testimony of her: “Mother Marie-Celestine has acquitted herself in a perfect manner of all the tasks that have been confided to her.” Returning after her triennium to the exercise of obedience and recollection, she tried to obscure herself entirely and we may say that she was no longer found except in choir or in her cell. It was about this time that with Father Passerat’s consent, she made the vow of always doing what she recognized as being the most perfect.

In 1847, the confidence of the Sisters called her once more to the task of Superior. This time, the tribulations came from the outside. The Revolution of 1848 had broken out. When they saw the signs of it, the Redemptoristines of Vienna omitted nothing to divert the anger of God. Continual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, prayers to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, penances – nothing was left undone, but the chalice of tribulation had been prepared and it had to be drunk.

Mother Marie-Celestine did it with an intrepid heart. On 6th April 1848, the insurgents assailed the Redemptorist convent in the morning. In the evening, at five o’clock, they attacked that of the Sisters, who scarcely had the time to flee through a breach in the garden wall. More than the others, the Superior was the object of pursuit by the rebels. She had to separate herself from her daughters and, with a broken heart, wander from one house to another belonging to the relatives and friends of the Sisters. And what did she not suffer then, seeing her daughters dispersed, denuded of everything, with no hope of being reunited again! Finally she found refuge with Baron Lago, the relative of one of her Sisters, and she remained in hiding in their house for the space of six weeks. She did everything she could to at least keep the property of the convent and the church, but it was all in vain. She even had to leave Vienna again in all haste with the family that had sheltered her. Soon afterwards, the suppression of the Order was decreed, and there was nothing else the poor Mother could do than rejoin some of her daughters who had found refuge with the Sisters of Saint Elizabeth at Aix-la-Chapelle, and who ardently desired her to come to them.

However, our divine Redeemer wished to draw good out of evil. The tempest which seemed to have destroyed everything determined the foundation of a new monastery in a country which had not possessed one before, and the convent of Vienna was soon able to be re-established. From Aix-la-Chapelle, the Sisters directed their steps to Holland, the hospitable land where since 1835 the Redemptorist Fathers had possessed at Wittem a former Capuchin convent founded in 1732, the same year that Saint Alphonsus had instituted the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer. In the village of Galoppe, not far from Wittem, a provisional monastery was being prepared for the Sisters, and Mother Marie-Celestine and her daughters made their entry there on 14th October of this same year of 1848. The enclosure was established. The next day, on the feast of Saint Teresa, the Sisters once more put on the habit of the Order, and everyone, after the first Mass celebrated in this sacred asylum, renewed their religious vows. The joy and gratitude of the Mother and her daughters was great and reached its peak when, after three years of waiting, the community was able to make its entry into the new Monastery of Marienthal, built in the village of Wittem, not far from the convent of the Redemptorist Fathers.

* * * * *

And now Mother Marie-Celestine had been chosen by God as the foundress of this new Monastery which was to give birth to many others, in particular the first Redemptoristine foundation across the Ocean. And she was to govern this house which until our own days has remained a model of regular observance, sanctity and apostolic spirit.

She fulfilled her mission with a zeal worthy of a true spouse of Jesus Christ, worthy of a privileged soul and endowed from her earliest years with very special graces. The Ven. Father Passerat, who visited her sometimes in her new abode, and the Superiors of the Convent of Wittem judged it necessary for her to continue exercising the functions of Superior, although her triennium had expired. The necessary dispensations were easily obtained. Under her government, the Monastery soon began to prosper. Her activity successfully faced all the difficulties in the beginning and soon the vocations came forward. The Order of the Redemptoristines having been re-established in Austria (1853), Mother Marie-Celestine generously made the sacrifice of two of her daughters, Mothers Marie-Victoria and Marie-Aloysia, the one being elected as the Superior of Ried and the other of Vienna. But God compensated her amply, so much so that, six years after her entry into Marienthal, the buildings were found to be insufficient to cope with the number of vocations, and they had to be extended.

Re-elected Superior in 1857, the good Mother then had a thought most worthy of her great heart. As a true daughter of the Church, she wished to console the heart of Pius IX by giving him news of the Monastery and asking for his holy blessing. Her letter was accompanied by several pictures painted by the nuns. Here is the text:

Most Holy Father,

“Sister Marie-Celestine of the Five Wounds of Jesus Christ, Superior of the Religious of the Most Holy Redeemer in the Convent of Marienthal, Diocese of Roermond, in Holland, - most humbly prostrated at the feet of Your Holiness, takes, in the name of her community, the respectful liberty of expressing to the Holy See and to the most worthy successor of Saint Peter the sentiments of profound veneration and entire devotion by which the spiritual daughters of Saint Alphonsus de Liguori are animated in regard to the common Father of the faithful.

“We always remember with a sweet consolation, Most Holy Father, the great part that Your Holiness played in the destiny of the Daughters of Saint Alphonsus at the time of trials in 1848, when they were victims of the revolution in the capital of Austria. Chased from Vienna, they took refuge in a solitary place in the Dutch province of Limburg, where, first of all renting a little house, they lived together in community, observing as far as was possible the Rules of their holy Institute. After surmounting many obstacles, we had the happiness of constructing a regular monastery with a little chapel. But what gave us the greatest happiness was that Your Holiness deigned, by a quite extraordinary favour, to bless our enterprise and grant our new foundation canonical approval, dated from 30th January 1852.”

Since this time, the Lord has filled us with graces, as although we are living in a Protestant kingdom, we nonetheless enjoy a happy liberty which has given us every facility for observing our holy Rules to the letter. Moreover, the Lord has favoured us with numerous and good vocations. Many persons from the best families in society have asked for and obtained their admission into our new monastery, delivering themselves now heart and soul to the contemplative life, the principal aim of our Order. We are already twenty five religious, and our monastery is no longer sufficient for so many requests for admission, and we see ourselves obliged to think of increasing the present buildings of our convent considerably, with the consent of our Most Reverend Bishop.

“So now we come before you very humbly to ask for Your Holiness’ blessing upon our new enterprise and especially upon the community of Religious Redemptoristines of Marienthal. So give us a place in Your paternal heart, Most Holy Father, and keep us always under Your beneficent protection. Thus united in heart and spirit to the visible Head of our Mother the Holy Church, we shall be able entreat the Father of mercies with greater confidence to fill Your Holiness with the consolations and graces necessary for the government of the Church. And in truth, we are already obliged by our holy Rules to offer up our prayers daily for the needs of the Church; but the numerous proofs of paternal charity that Your Holiness has given us up till this moment, leads us and obliges us in a particular manner to say special prayers for the happiness and preservation of Your sacred person.

“And so, Most Holy Father, please accept the sentiments of gratitude, respect and devotion that Your spiritual daughters of Marienthal offer You. Humbly prostrated at the feet of Your Holiness, I dare once again to reiterate my respectful request for You to give me Your holy blessing, and to also especially bless each one of my spiritual daughters.

“With the most profound respect,

“Your Holiness’ most humble and obedient servant.

“Sister MARIE-CELESTINE of the five sacred wounds of Jesus Christ.”

Marienthal, 21st March 1858.

This letter was to go straight to the paternal heart of Pius IX. The holy Pontiff deigned to send the following reply on 14th July of the same year. We translate it from the Latin.

PIUS IX, Pope.

To our dear Daughter Marie-Celestine of the five sacred Wounds of Jesus Christ.

“Dear Daughter in Jesus Christ, greetings and apostolic blessing.

Your letter of 21st March last has reached us. It is a new and dazzling witness of your filial devotion towards us, your faith, your piety and your obedience. It has mitigated the sorrow that we experienced long ago when we learnt that in the very grave political troubles, turbulent and seditious men chased you away from your house in Vienna and sent you into exile. It has been a great consolation for us to learn from your letter that in the midst of these troubles and tempests you have been able to find a safe and tranquil asylum in Holland where you can attend in peace to the duties of your holy state, and where your religious Institute has recruited numerous vocations. Blessed be God, the Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ, whose Providence has thus determined many people to let themselves be guided by the example of your virtues and embrace religious life!

“You must thus recognize all the blessings of the divine clemency with the greatest zeal and walk with the greatest eagerness in the way of perfection. Apply yourselves with all your powers, my dear daughters in Jesus Christ, to practise these virtues which have cast the greatest lustre on this brilliant model of sanctity, Saint Alphonsus de Liguori, your Father. Never once cease to honour and serve, with an entirely filial zeal and piety, the most holy Mother of God conceived without original stain, through whom God willed all graces should come to us continually. Remember also every day in your prayers our own feebleness, so that our actions and efforts may contribute to the greatest glory of the name of God and the good of all the faithful.

“As a measure of Our paternal charity, for you and your companions, and as a harbinger of heavenly grace, We give you with Our love, to both you, dear Daughter in Jesus Christ and to all your Sisters, Our apostolic blessing.

“Given at Rome, the seat of Saint Peter, on 14th July 1858 in the thirteenth year of our Pontificate.

“PIUS IX, Pope.”

This letter from the Vicar of Jesus Christ was a great consolation for the faith and apostolic zeal of Mother Marie-Celestine and encouraged her singularly in the exercise of her charge. And indeed she was re-elected Superior in 1863 and 1871, in spite of her sickly state. This languor began in 1859, at the time of the first death that took place in the new monastery. A remarkable circumstance marked this first departure for heaven. In 1849, and at the beginning of the foundation, Mother Marie-Celestine had instantly asked the Lord not to let any Sister die before ten years had elapsed, and this was to let the community be established solidly. She was heard to the letter, but at the same time she received, until her death, the prerogative of bodily sufferings which often confined her to a bed of sorrows. The death of her long-time companions and the departure of two other Sisters for the Convent of Vienna which was then suffering, were all new crosses for her heart. These crosses, it is true, found some compensation in the joy of a new foundation established at Sambeek in Dutch Brabant in 1874. Thirteen Sisters were sent there. Mother Marie-Celestine succeeded in the same year in dissuading her daughters from their plan to re-elect her, and she even begged the Bishop of Roermond not to grant the dispensation required. She was named Mother Vicar, and while she was exercising this charge, she suffered the terrible trial of the year 1877, when the Convent of Marienthal became the prey of flames. The poor Mother, suffering and confined to bed, was brought by the Countess of Ansembourg to her mansion at Galoppe. When she felt a bit better, she joined her Sisters who had found refuge near Maastricht, and re-entered Marienthal with them in the month of October 1877.

From this time on her life was simply a long succession of sufferings. According to the doctor, her last long illness was accompanied by sorrows such that the doctor had never seen greater. To these exterior pains was added an interior abandonment which afflicted her to a supreme degree. Since she was thirty she had never tasted consolations, but this time, it was rather a moral agony to which no one could supply a remedy. And yet, in the depths of this resolute soul, the Lord imbued a powerful grace that sustained her without her realising it and helped her prepare herself for her eternal wedding. This sorrowful preparation, according to God’s plan, was to replace the religious help which ordinarily was not lacking in the monasteries. The death of Mother Marie-Celestine was most unusual. On 12th December 1878, the community was reciting the Office of the Dead for a Sister who had died at Sambeek. Suddenly some noises could be heard coming from the Infirmary. They ran there in all haste and found the dead body of Mother Marie-Celestine sitting in her chair, dressed in the habit of the Redemptoristines. She had reached the age of seventy, and she had spent nearly fifty of them in the Order of the Most Holy Redeemer.

A wise and strong woman, a great and generous soul, with a tender and solid devotion, endowed with a sure and practical common sense, full of faith and a very active love, she was, for nearly half a century, the pillar and strength of the Order of the Redemptoristines beyond the Alps. As a Superior, she united a very maternal goodness and tenderness with a wise rigour for the observance of the Rules, always avoiding the extremes. She had a special talent for consoling the afflicted and souls who were tempted. In her general conduct there was nothing arrogant, nothing hard or harsh. Cheerful and gentle in conversation, she made the best impression on strangers.”